For Casa Loewe Barcelona, Jonathan Anderson commissioned a site-specific installation from Japanese bamboo artist Tanabe Chikuunsai IV. It opens to a patio displaying a sculpture by South African ceramicist Zizipho Poswa.

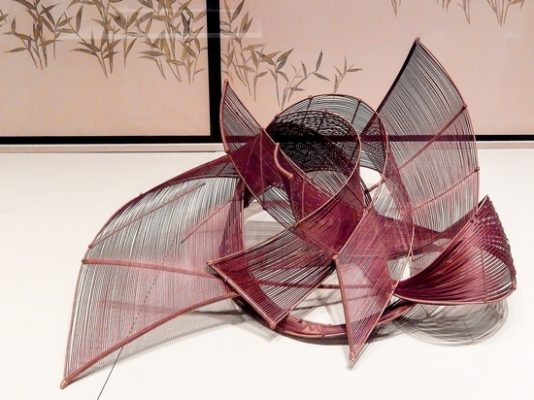

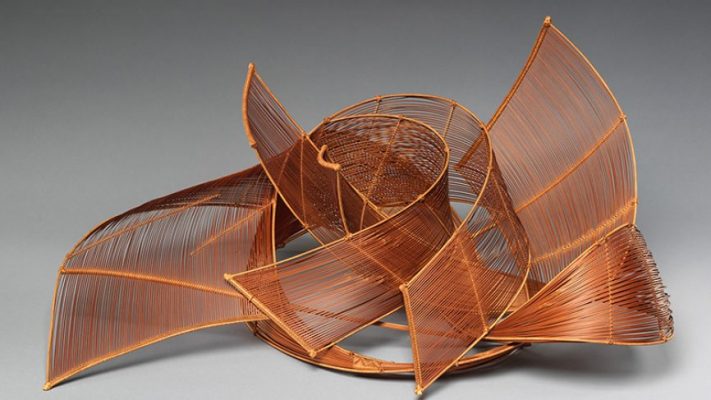

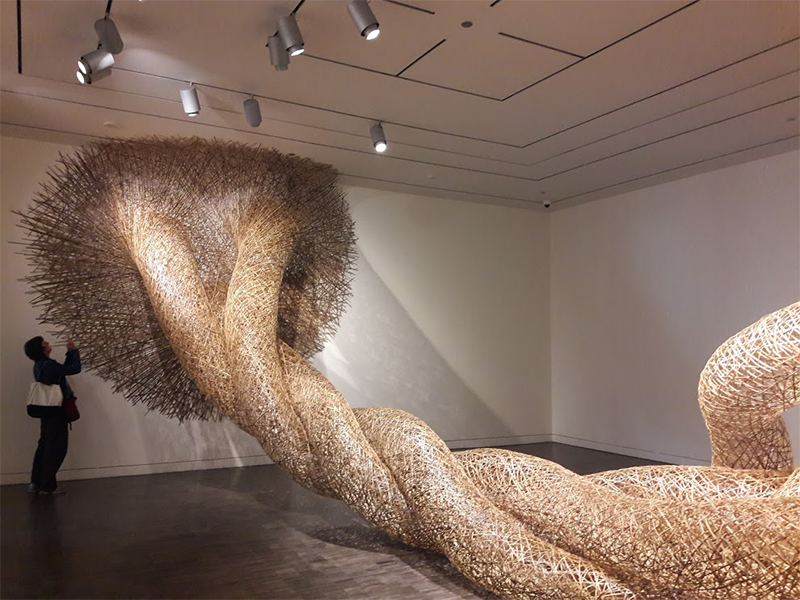

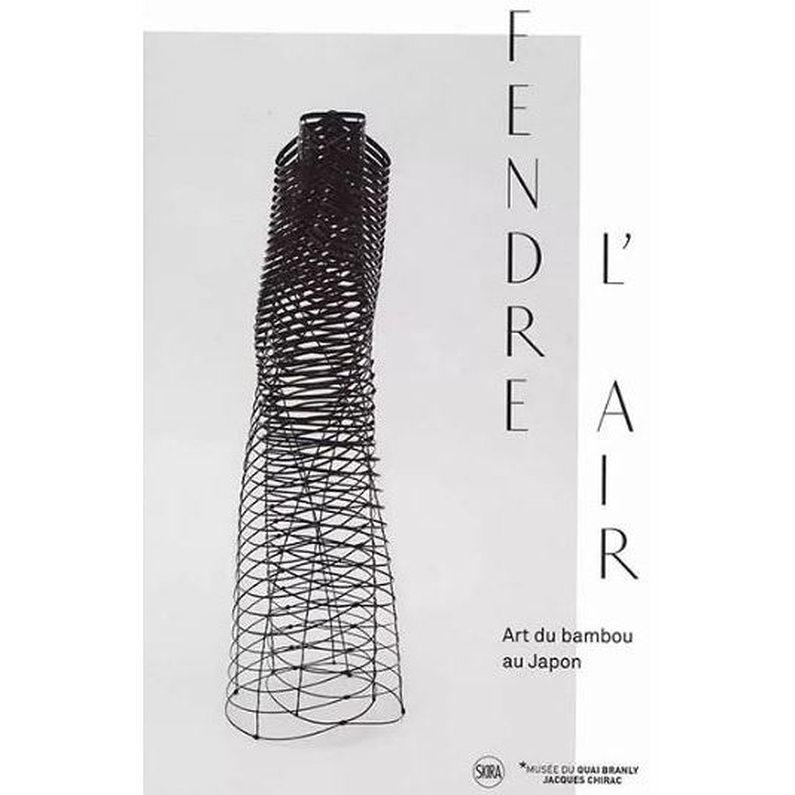

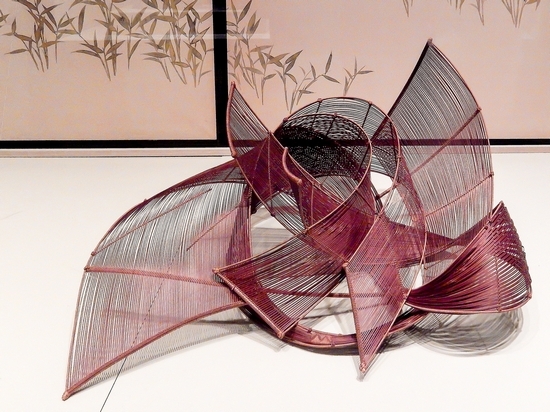

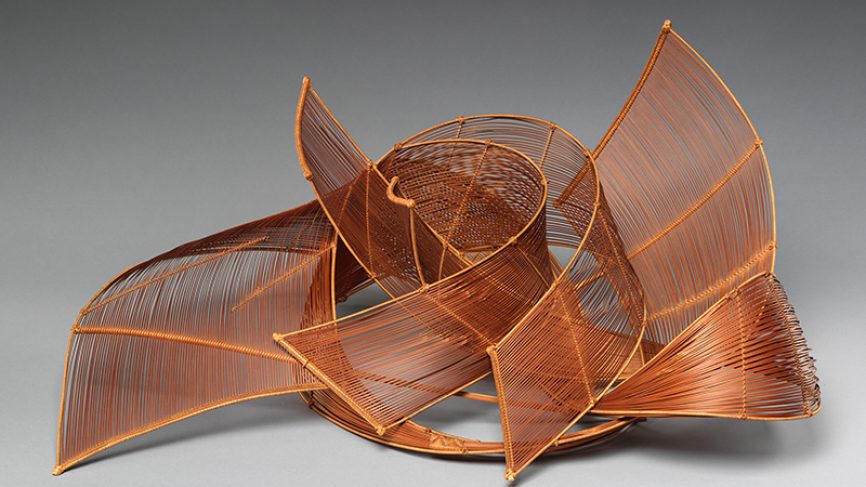

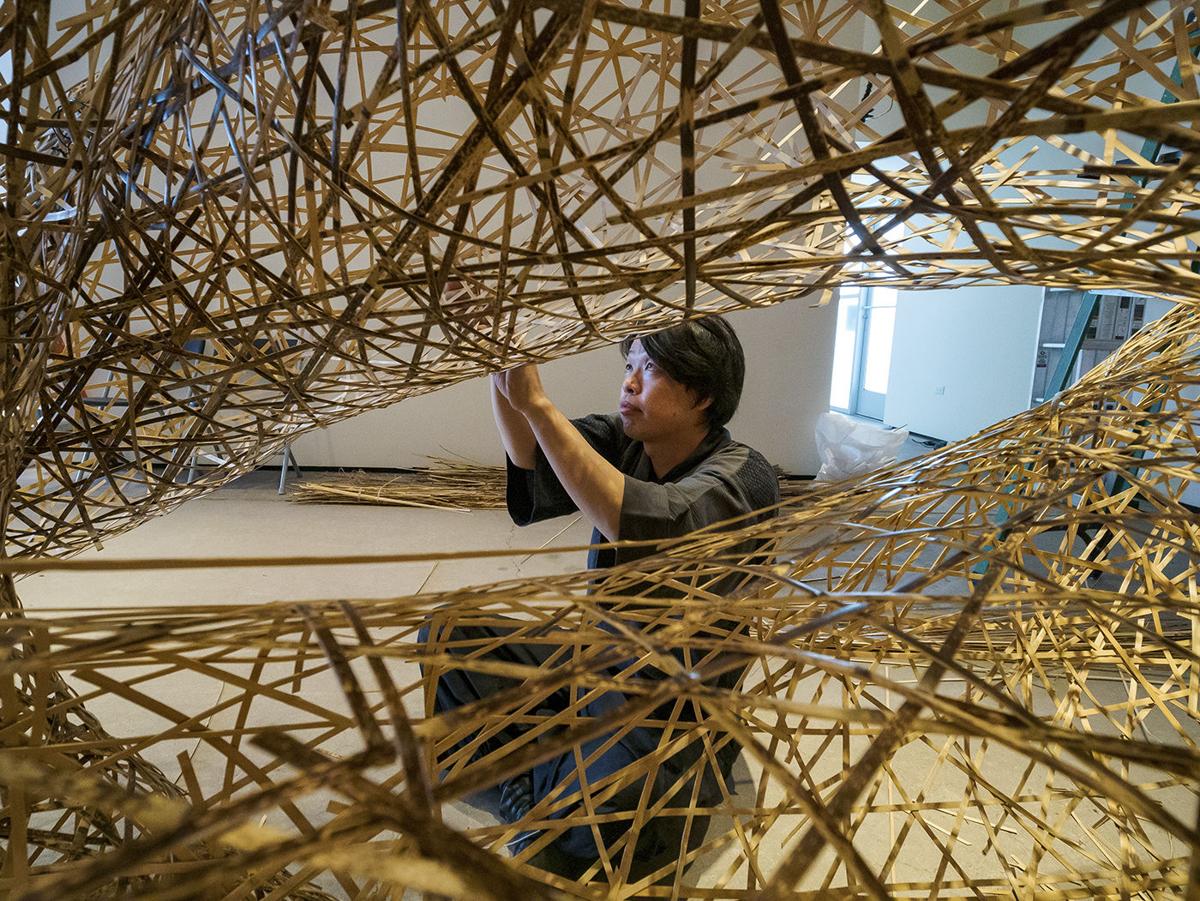

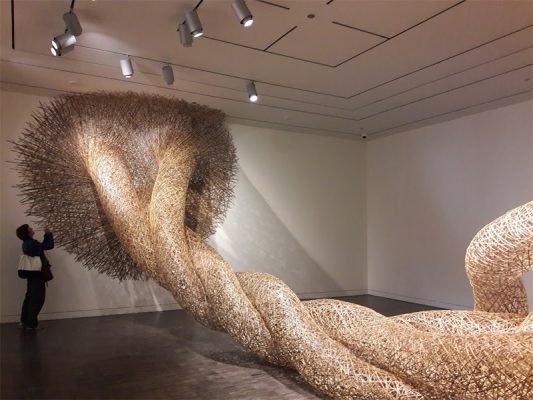

Osaka-born artist Tanabe Chikuunsai IV works with torachiku, a striped “tiger bamboo” that only grows in one valley of Kōchi Prefecture, in the south of Japan’s Shikoku island. Following in the footsteps of three generations of bamboo craftsmen, he weaves strips of it into sculptures held together by sheer tensile strength to realize monumental works that have been collected by the British Museum and the Met—and, most recently, by Loewe.

“I wanted to show his work for some time, but we needed the right space,” said Jonathan Anderson, who joined the Spanish luxury goods house as creative director nearly a decade ago. “It felt perfect for the volume of Barcelona.”

Anderson was referring to Casa Lleó i Morera, “one of the most emblematic buildings of Lluís Domènech i Montaner and of Catalan Modernism,” he said. It is home to the brand’s flagship, Casa Loewe Barcelona, which just reopened after a major redesign.

During renovations, the team discovered and restored the building’s original frescoes and gold-leaf ceilings, which were left exposed above Loewe’s latest fashion collections. The space also showcases antique and contemporary furnishings by Axel Vervoordt and Gerrit Thomas Rietveld—along with a specially commissioned, site-specific installation from Chikuunsai.

“The first time I entered a grove of torachiku I was awestruck,” the artist told Artnet News. “It is my hope to preserve such beauty for future generations. They emitted a mystical ambience, and the energy coming from within me fused with the bamboos.”

Now, Chikuunsai’s work is fused with the walls of Casa Loewe Barcelona, where it appears to have grown into a canopy beside a vertical indoor garden. “It highlights the synergy between nature and the handmade,” Anderson told Artnet News.

Under Anderson’s helm, the house has embraced all things art, design, and craft. Its stores function as quasi-galleries for its growing collection of works, and its annual Loewe Foundation Craft Prize is now in its fifth year (the winner will be announced June 30, coinciding with an exhibition at the Seoul Museum of Craft in South Korea).

At Casa Loewe Barcelona, Chikuunsai’s installation is hardly the only art on display.

Haegue Yang’s The Intermediate: Dangling Hairy Hug will greet you at the entrance, alongside a stained-glass window by the Turner Prize winner Richard Wright. Walking through the 5,500-square-foot space, you’ll encounter everything from a large-scale macramé work by the late Spanish Modern artist Aurelia Muñoz hanging from the ceiling down to the lower floor, to sculptures by Richard Tuttle and 2022 Craft Prize finalist Takayuki Sakiyama.

The store also houses Loewe’s largest collection of hand-painted stoneware by Pablo Picasso, spotlighting the artist’s work as a ceramicist. “He started making these pieces after a 1946 visit to the annual pottery exhibition at Vallauris,” Anderson said.

Meanwhile, Catalan crafts have been woven into the space, between the floors of local terracotta and the ceramic walls and columns that have been handcrafted by artisans from the Granollers-based Ceràmica Cumella in Mediterranean shades of white and blue.

Tanabe Chikuunsai IV, site-specific installation at Tai Modern, photo Gary Mankus

Tanabe Chikuunsai IV, site-specific installation at Tai Modern, photo Gary Mankus Tanabe Chikuunsai IV at work, photo Incredible Films

Tanabe Chikuunsai IV at work, photo Incredible Films

Tanabe Chikuunsai IV, Connection. Photo by Jonathan Curiel.

Tanabe Chikuunsai IV, Connection. Photo by Jonathan Curiel.

Photo © Éric Sander

Photo © Éric Sander Photo © Éric Sander

Photo © Éric Sander Photo © Éric Sander

Photo © Éric Sander