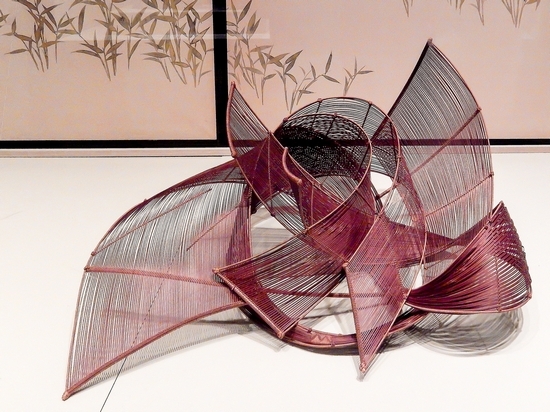

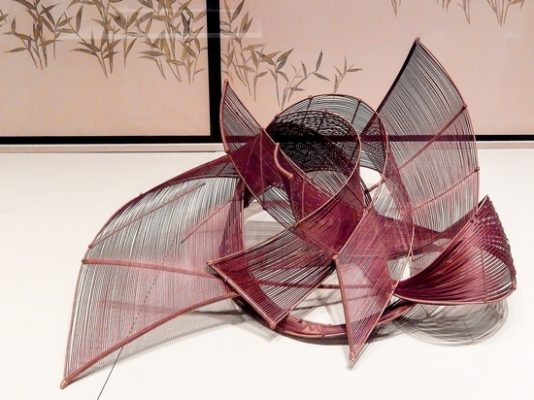

Left to right: Chikuunsai Tanabe IV’s “GATE” (2019) and Kenichi Nagakura’s “Flower Basket, ‘Woman (A Person)'” (2018) | © T. MINAMOTO; THE ABBEY COLLECTION, PROMISED GIFT OF DIANE AND ARTHUR ABBEY TO THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART. IMAGE © THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART

The Abbey Collection of bamboo arts and crafts, the 20-year loving labor of New York collectors Dianne and Arthur Abbey, attracted 470,000 visitors when it showed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, in 2017-18. A traveling exhibition of some 75 pieces, which is now making a stop at The Museum of Oriental Ceramics, Osaka, makes for captivating and edifying viewing.

Japan’s ubiquitous bamboo is unsurprisingly storied. Woven artifacts evidence from the later Jomon Period (10,000-200 B.C.). The ancient nation- and culture-building texts, the “Kojiki” (Records of Ancient Matters) and “Nihon Shoki” (“The Chronicles of Japan”), record bamboo knives and combs with magical powers. The oldest surviving baskets are 8th-century offering trays kept in the Shosoin treasure house in Nara. Bamboo was obviously crucial to the 10th-century prose narrative “Taketori Monogatari” (“Tale of the Bamboo Cutter”). Tea masters of the 15th century revered seemingly artless utensils in their burgeoning spiritual practice. Emperors were gifted the choicest of bamboo wares.

But it was only comparatively recently that bamboo crafting became considered fine art. The exhibition’s chronology from the 19th century indicates how this came about by participation in Japan’s National Industrial Exhibition and the world fairs.

Hayakawa Shokosai I (1815-1897) engraved his name on his pieces — Edo Period (1603-1868) craftsmen did not do this. One of his lidded baskets won the Phoenix Prize in the first National Industrial Exhibition in Tokyo’s Ueno Park in 1877, then was acquired by the Empress Shoken. Hayakawa’s plaited “Bowler Hat” (ca. 1880-90s) was a favorite of the Meiji Era (1868-1912) kabuki performer, Ichikawa Danjuro IX (1838-1903).

Tanabe Chikuunsai I (1877-1937) received an award at the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris in 1925 — the showcase that introduced Art Deco to the world. This reception suggested bamboo artists could acquire the recognition Japanese ceramic and lacquer artists had previously achieved. Tanabe’s “Ryurikyo Hanging Flower Basket” (1900-20) was made after studying the baskets in works by the literati painter Yanagisawa Kien (1704-1758).

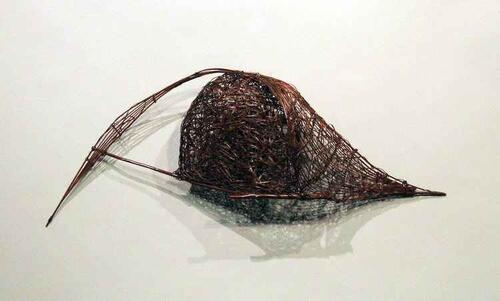

Individual creative flourishes followed in the Showa Era (1926-89), like Monden Kogyoku’s abstracted circular “Wave” (1981). Such pieces pushed craft further into art territory. But it was not until 1985 that there was even a significant historical review in Japan, “Modern Bamboo Craft: Developments in the Modern Era” at The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo.

Overseas collectors assumed some of the mantle. California’s Lloyd Cotsen (1929 -2017) assembled a vast collection of basketry that showed around America before being donated to the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco in 2002. Argentinian Guillermo Bierregaard created a museum for his collection in Buenos Aires 2006. The Stanley and Mary Ann Snider Collection went to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Now the Abbey Collection is a promised gift to New York’s Met.

Further exhibition pieces extend into the entirely contemporary. Kenichi Nagakura (1952-2018) is represented by an elongated personification, “Flower Basket, ‘Woman (A Person)” (2018), and an interdimensional wormhole-type construction, “Gate” (2019) by Tanabe Chikuunsai IV, is installed in the museum lobby. Intensified focus will fall further on Tanabe IV in May through June, then in July, with his solo exhibitions scheduled for the Osaka and Nihonbashi Takashimaya department stores.

“Japanese Bamboo Art from New York: The Abbey Collection” at The Museum of Oriental Ceramics, Osaka, runs through April 12; ¥1,200. For more information, visit www.moco.or.jp/en.