Original article at Asian Art Newspaper.com

THE MUSEUM OF Fine Arts in Boston has recently received a transformative gift of over 90 pieces spanning the late 20th and 21st centuries, given by collectors Stanley and Mary Ann Snider from their Japanese art. This continues the tradition of collectors of Japanese art making donations to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MFA), that have included such gifts from Ernest Fenollosa and William Sturgis Bigelow. Stanley and Mary Ann Snider represent a new generation of Bostonians who want to ensure that visitors to the museum will understand the vibrancy of Japanese art and culture in our own time by viewing their collection of ceramic and bamboo art.

This exhibition, curated using their recent gift, highlights the craftsmanship and highly creative sculptural forms of Japanese decorative arts. Among the first exhibitions to present contemporary ceramics alongside baskets, Fired Earth, Woven Bamboo offers an in-depth look at 60 objects created by dozens of leading artists based in Japan. Many of the works are on view for the first time and are enhanced by a selection of contemporary textiles, screens and paper panels.

During the late 19th century and into the 20th century, ceramics and bamboo arts in Japan evolved from traditional crafts into modern art forms, as those who produced them evolved from craftspeople into artists. As modernisation continued, a new generation of artists began to assume creative control over the works they produced, creating unique pieces with their own hands, based on their own ideas. Creativity – rather than mere technical excellence – became the standard for an artist’s work. In ‘basket with bamboo-root handle’ (1930s), for example, Maeda Chikubosai demonstrates an early example of bamboo art as a form of personal expression.

In the years following World War II, avant-garde clay artists in Japan declared that their work no longer had to take the form of traditional vessels. Many of these artists maintained respect for ancient methods and aesthetics, while embracing the non-functionality of their ceramics. The earliest generation of contemporary ceramic artists live through a major turning point in the history of the medium: a shift in creative control from kiln foreman or craftsman to artist, and the ensuing evolution of ceramics from commercial products to works of art. Beginning in the early 20th century, leading ceramicists, while still influenced by traditional approaches, explored the medium as a means of self-expression and gave shape to their own aesthetic sensibilities by working directly with the materials. Akiyama Yo intentionally exploited deformations that would be considered defects in commercial products with Untitled MV-1019 (2010), which purposely employs cracks in the clay to provide a weathered effect. Fukami Sueharu, who brought Japanese ceramic arts to global attention, also adopted inventive approaches to traditional techniques. His The Moment (Shun) (1998) is a keenly edged abstract work of porcelain that slices through space like a knife.

Recently, international praise has centred on pioneering female ceramists. Until the post-war era, virtually no women in Japan were ceramic artists; men feared that the presence of women would pollute their kilns. Koike Shoko was one of the first female graduates of the ceramic department at Tokyo National University of the Arts. Her shell-shaped vessels, such as Shell 95 (1995), were first thrown on a wheel and then sculpted from the clay of the Shigaraki region. Whereas traditional Shigaraki vessels are left unglazed, Koike applies layers of white slip (liquefied clay) to the surface. Sakurai Yasuko, also among the first women to work with clay on a university campus, plays with forms that make the viewer aware of light and shadow in Vertical Flower (2007).

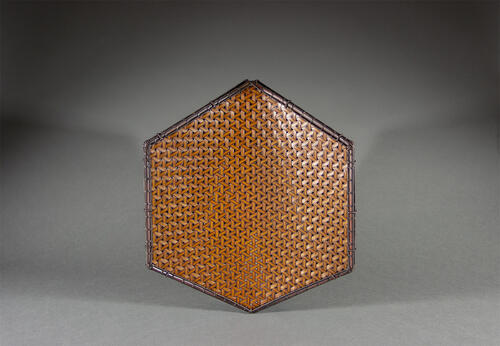

In contrast to ceramic art, contemporary bamboo art continues to be dominated by artists who were trained through apprenticeships, often in regions where bamboo work has traditionally flourished. During the last century, however, the medium has seen great change. Since the 1950s, Japanese bamboo artists have created highly original pieces that transcend utilitarian use and represent independent works of sculpture. Contemporary bamboo art continues to be dominated by artists trained in the facilities or apprenticeships in regions where bamboo work has traditionally flourished, including Oita, Osaka, Shizuoka, Tochigi, and Niigata. Most of the artists whose works are collected (in this exhibition) were trained in or are active in these regions. Despite this adherence to tradition, the medium has greatly evolved and diversified over the last century. As bamboo art focuses not on the application of decoration, but on fashioning the form of the object itself, it calls forth more radical originality from artists seeking innovation. In the late 19th century and early 20th centuries, the making of Chinese-style baskets flourished, primarily in Osaka, against a background of sencha (tea) ceremony culture. Soon, as with ceramics and other crafts, those who made bamboo works began to gain recognition as artists rather than merely as craftsmen.

By the 1920s, bamboo artists had begun to show their work in public exhibitions such as the Japan Art Exhibition (Nitten), and from the 1950s at the Japan Traditional Art Crafts Exhibition, which demanded originality from participants.

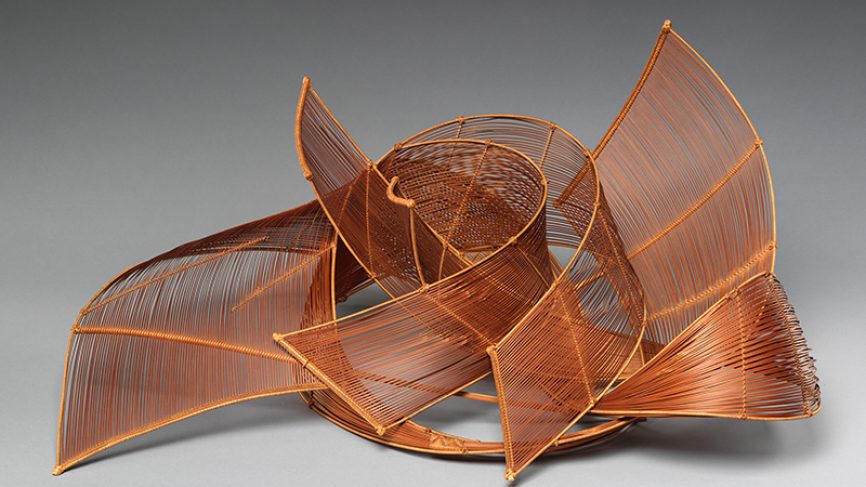

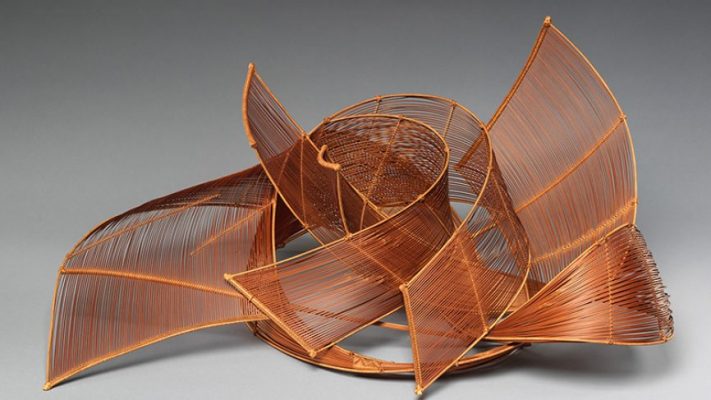

A novelty introduced by artists working in the style where curving forms predominate is the appearance of quasi-architectural structures, composed of straight lines. This is illustrated in Yako Hodo’s piece in the exhibition – Late Autumn. The more daring and experimental work is done by artists exhibiting in shows such as the Japan Art Exhibition and the Japan Contemporary Arts and Crafts Exhibition, along with other artists who are not affiliated with any arts and crafts organisations. Among the artists in this category are Torii Ippo, Honma Hideaki, Watanabe Chiaki, Yamaguchi Ryuun, Shono Tokuzo, Honda Shoryu, Morigami Jin, and Mimura Chikuho. These artists often generate a unique and lyrical sense of movement in their work through the spatial properties of braided structures that make dynamic use of the material’s pliability and elasticity.

In Fire (2011), Yamaguchi Ryuun displays his creative approach by leaving the ends of strips of bamboo unbound, allowing them to spread out and create a voluminous form. Morigami Jin produces shapes that are possible only in bamboo sculpture, his Red Flame (2007) is vessel-like but is transformed into an expression of lines and silhouette in brilliant colours. The development of bamboo works as art – freed entirely from functional use as vessels or baskets – can also be seen in works by Fujitsuka Shosei. Fujitsuka’s pieces span a range from useful objects such as lampshades to the minimalist, elegant flames of Fire (mentioned above). Tori Ippo’s undulating works are far from traditional, functional wares. His Flight (2003), features complex, contrasting bands of twisting bamboo that arc and command the space around them. Another novelty introduced by contemporary bamboo artists, where curving forms predominate, is the appearance of quasi-architectural structures composed of straight lines, such as Yako Hodo’s Late Autumn (2004).

Until 8 September, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, www.mfa.org.