Ravens soar, nest and forage all around us.

In the morning, they fly to the foothills of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, then head back toward town, where they drink, bathe and preen while croaking and cawing at each other.

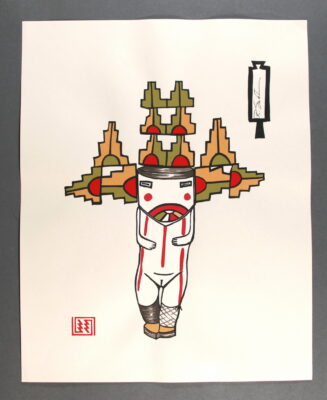

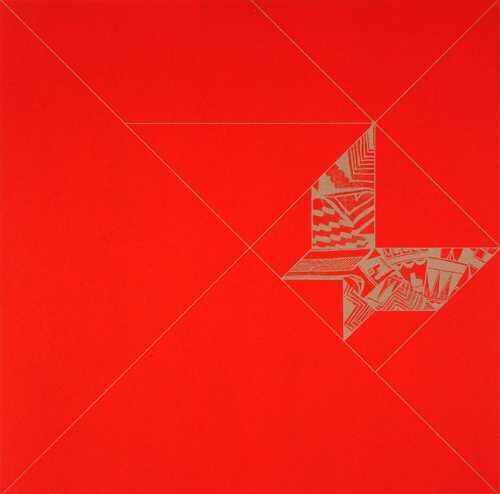

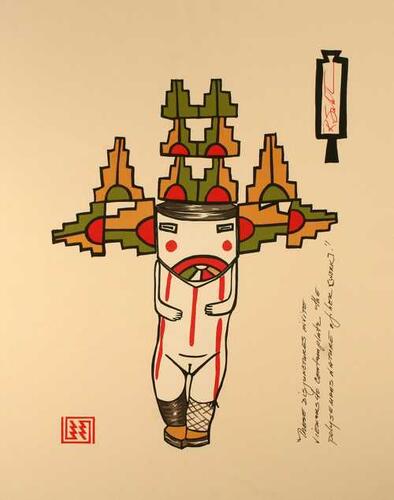

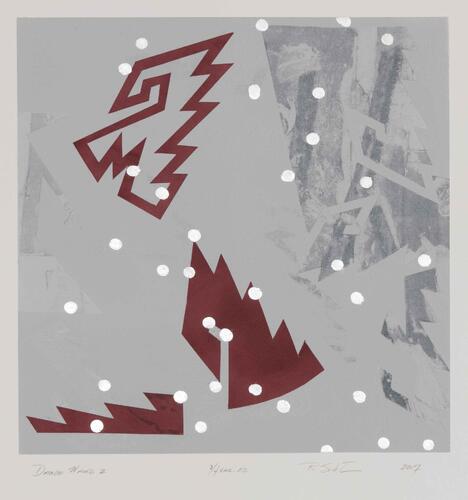

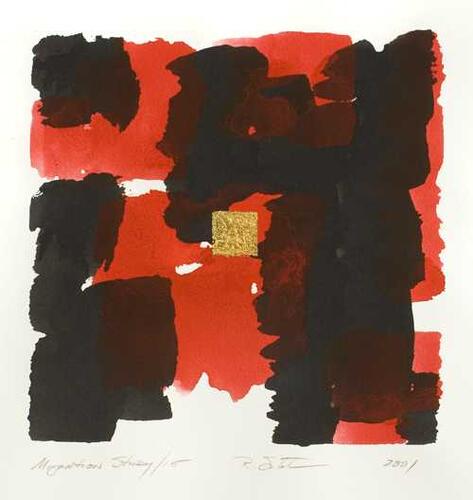

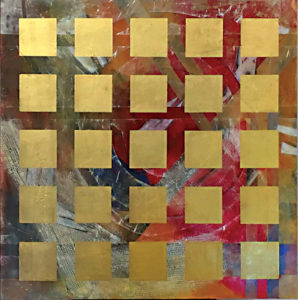

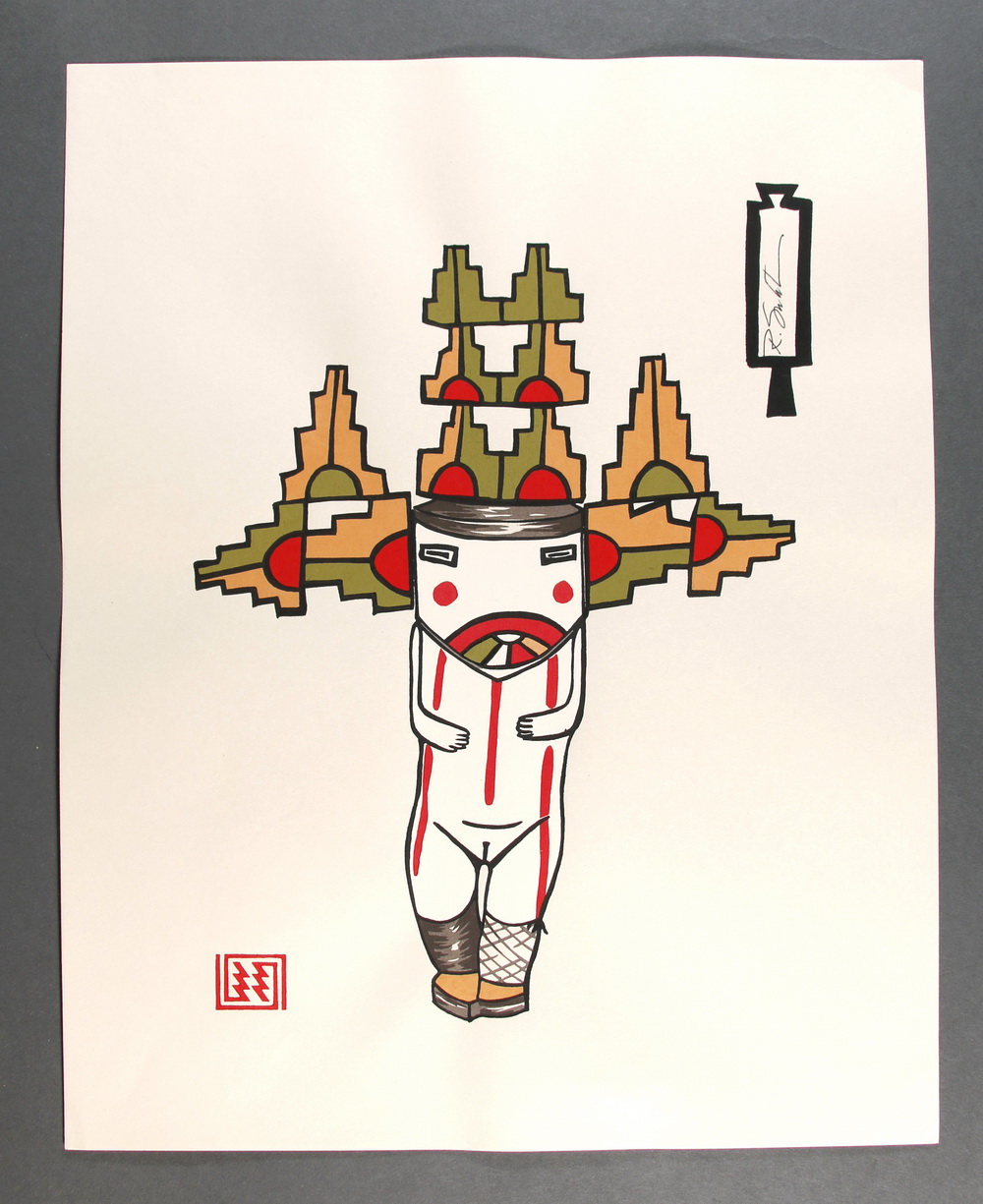

Ramona Sakiestewa was fascinated by the ravens flocking in her Santa Fe yard. Her insights produced the series of monoprints “Raven @ the Big Bang,” on view at Tai Modern from Aug. 13-30.

“They’re very entertaining,” she said. “They’re loud and I have a little pond in the back and they bathe and bring their young to the pond the next year.

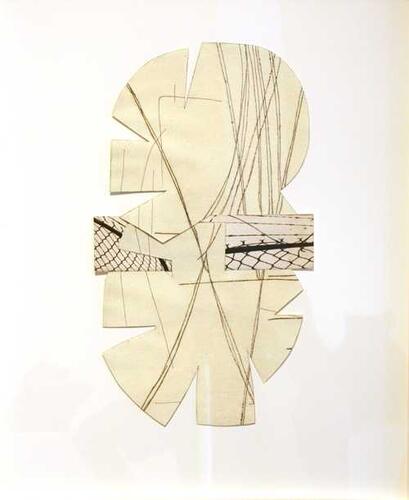

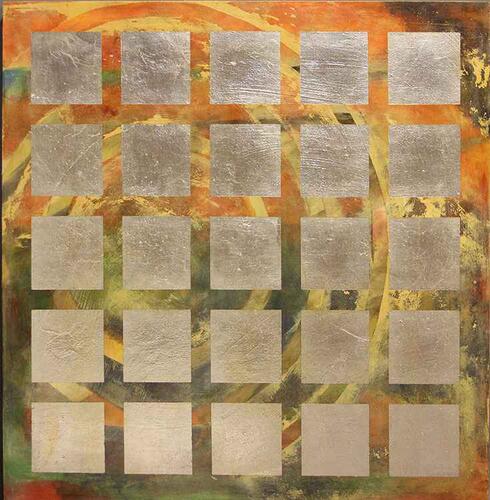

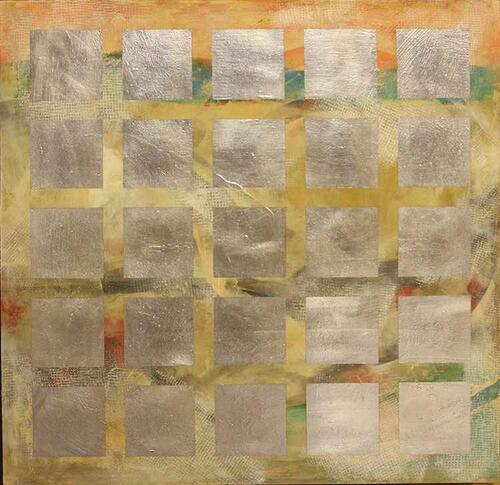

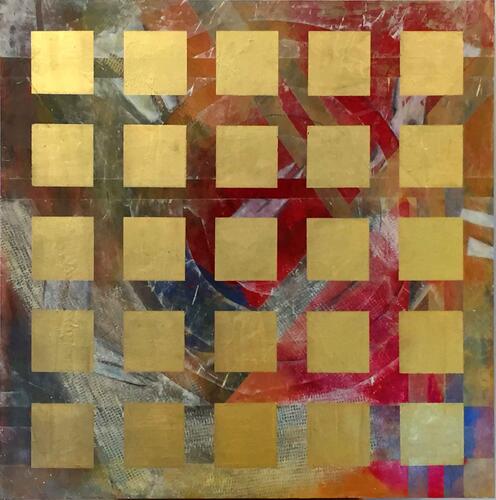

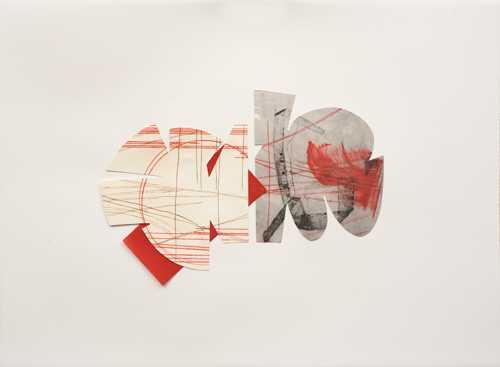

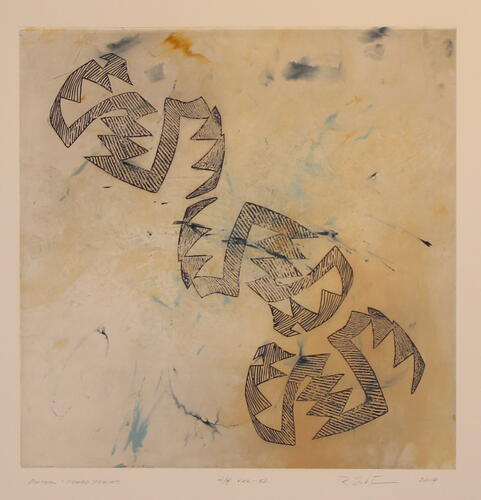

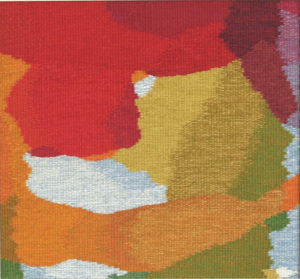

In her latest work, she combines the texture of fabric and papers with prints and painting to make works sometimes sewn together into layered color and images.

Sakiestewa is Hopi; ravens figure prominently in Native American culture. The second half of the exhibition’s title reflects Sakiestewa’s belief that the birds have existed since the Big Bang.

The artist grew up in Albuquerque, where she attended Bandelier Elementary and Wilson Junior High. She had always been interested in the arts and making things.

“I loved sewing,” Sakiestewa said. “When I was like 5, I got a little Singer sewing machine and I made doll clothes.”

By the time she was in second grade, she was stitching her own clothing.

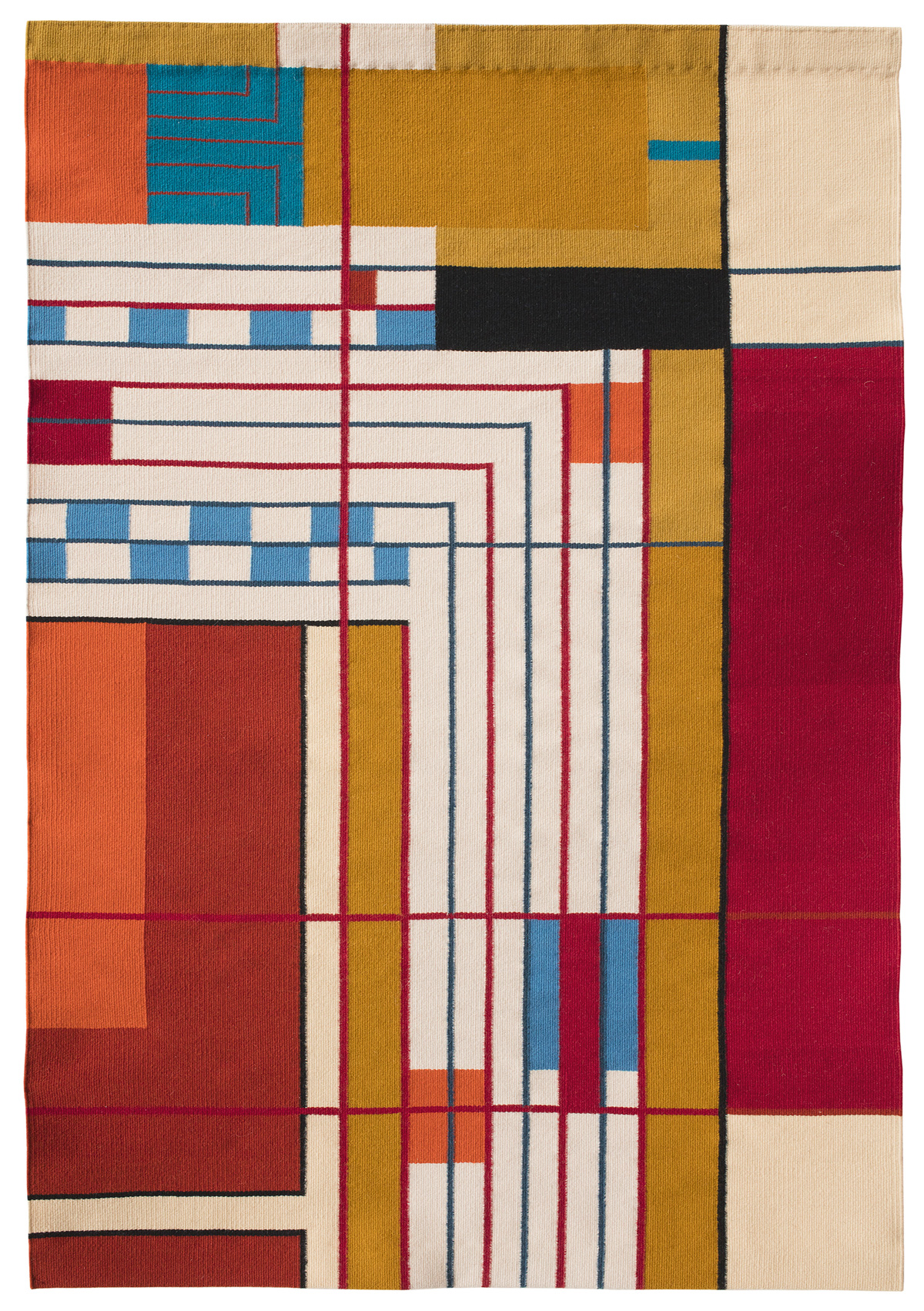

Fiber and texture feature prominently in her work. A former weaver, Sakiestewa added fabric to the printing plate of her raven pieces, tore it up, then reconstructed it with her own painting in Japanese inks.

“I like constructing and deconstructing them,” she said. “Sometimes I sew them back together because paper’s sort of like fabric. I sewed the wings on.”

The series also features sandhill cranes, images from a scene the artist witnessed in Utah.

“It’s about an event I saw when a group of cranes were grazing in a field. A hawk was circling above them. Literally, they flapped their wings and lifted off the ground and then they flew in a circle facing inward with each circle, their long legs hanging down. They made a vertical column as they rose up in the sky and the hawk left them alone. It was like watching a 747 take off vertically.”

A fiber and texture fan, Sakiestewa shops by feeling the fabric on the clothes rack. She studied textiles at New York’s School of Visual Arts and was known as a tapestry weaver until the 2008-2009 recession.

“The gallery owner died,” she said. “The economy had tanked and you could see people pulling away from collecting.”

She began experimenting with print work. For more than 30 years she has written and lectured about Native American weaving and contemporary art, including a lecture tour of Japan. Her weavings hang in numerous corporate, private and museum collections. She also has worked with a series of nationally known architects designing for buildings and their interiors. She has worked in stone, metal, carpet and glass. Some of her work can be seen in the Tempe Center for the Arts in Arizona, Marriott Hotels in California and Washington, D.C., and in the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C.

She isn’t sure where her work will go next.

“I really like this whole bird figure,” she said. “It might be some different birds or something more abstract.

“I like making things,” she continued. “I’ve had jobs where the only product I had at the end of the day was a nice contract. It’s a kind of problem solving.”

Sakiestewa was awarded the New Mexico Governor’s Award for Excellence in the Arts in 2006 and was inducted into the New Mexico Women’s Hall of Fame.

The word creativity defines artist Ramona Sakiestewa. During a recent interview in her airy, contemporary studio in Santa Fe, Sakiestewa seems surprised at the suggestion that she is perhaps the most versatile of all Native American artists working in the United States. Decisive, willing to take huge chances, yet also very deliberate, methodical and modest, she responds, “I used to worry about ‘staying in my lane’ because most artists work in a single discipline, but I like trying everything.”

The word creativity defines artist Ramona Sakiestewa. During a recent interview in her airy, contemporary studio in Santa Fe, Sakiestewa seems surprised at the suggestion that she is perhaps the most versatile of all Native American artists working in the United States. Decisive, willing to take huge chances, yet also very deliberate, methodical and modest, she responds, “I used to worry about ‘staying in my lane’ because most artists work in a single discipline, but I like trying everything.”

Back in New Mexico, Sakiestewa spent several years as the minority arts coordinator for the state. Working with the Española Weavers Guild, she helped secure a major grant for the group and provided ideas on how and where they could host exhibitions. She realized that if she could help others launch an arts career, she could do so herself. “I could see the roadmap,” she says. “My arts administrative work was not personally fulfilling. I wasn’t making anything, or creating. So, I quit my job, borrowed money from my father-in-law to launch my weaving business and dove in. I managed to pay him back in three years.”

Back in New Mexico, Sakiestewa spent several years as the minority arts coordinator for the state. Working with the Española Weavers Guild, she helped secure a major grant for the group and provided ideas on how and where they could host exhibitions. She realized that if she could help others launch an arts career, she could do so herself. “I could see the roadmap,” she says. “My arts administrative work was not personally fulfilling. I wasn’t making anything, or creating. So, I quit my job, borrowed money from my father-in-law to launch my weaving business and dove in. I managed to pay him back in three years.” Many other architectural projects followed, from designing floor carpets to core master planning, including a project in Kurdistan, for Marriott Residence Inns in California, the

Many other architectural projects followed, from designing floor carpets to core master planning, including a project in Kurdistan, for Marriott Residence Inns in California, the