Santa Fe Reporter

By: John Photos

Published April 2008

Collage may be the most relevant medium for contemporary culture. The cutting up and repurposing of discarded and obsolete print media is the artist’s version of recycling and sustainability. It reflects thriftiness, a clever way to pinch pennies in a time of job instability and tightened belts. But collage also is a distillation of the way we consume information in pieces and without much context. From playlists to video clips to “news” websites that cater to demographics, information is as modular and customizable as any other possession.

That said, due to its dependence on paper, collage might also be one of the least relevant mediums. Now that the iPad is finally out, I don’t think it will be long before print media is viewed as hopelessly static and, from an environmental standpoint, deeply unethical. Some people will hang on to books as a sort of novelty (“books have a warmer voice”), but most anything with pages will be out on the curb. When this happens, don’t be surprised if you see Lance Letscher out there pawing through your stuff.

Letscher is a collage artist and, as one might expect, a major component of his practice is the collecting of raw material. Stories abound about favorite Austin, Texas, dumpsters into which he dives. He is a one-man salvage yard, rescuing the things that can’t even be donated in order to use them for parts. From the look of his works, his collection is extensive.

In a strange act of symmetry, Letscher puts out print media of his own. His solo exhibition, The Perfect Machine, coincides with the release of Letscher’s book of the same name. On view at Eight Modern are the original works that were created to accompany the story he wrote about a boy who sets out to make the eponymous contraption.

The publication is billed as a children’s book, but the imagery, which ranges from abstract to wildly abstract, may prove difficult to interpret. It requires a good imagination, to say the least, to reconcile what is depicted with what the story claims is depicted. Hopefully, kids will be drawn to Letscher’s kinetic style, which resembles nothing so much as the limitless permutations of Legos. I say hopefully because the story presents some complex ideas very simply. Really, The Perfect Machine is a celebration of the artistic impulse and the creative mind.

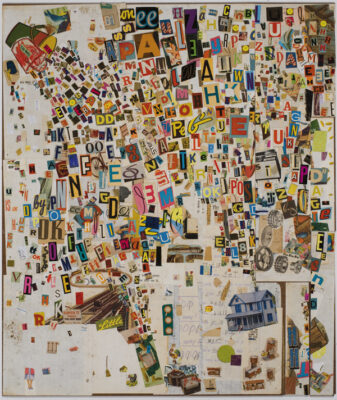

Letscher’s work is exemplary for its lack of cohesion. When I think of collage, it is typically an attempt to produce something new, something whole, from disparate parts. A lot of its power comes from unexpected juxtapositions and combinations of elements. Its use of existing and recognizable forms translates well to political satire or critique. Connotations are almost unavoidable. Yet, Letscher’s works are disjointed enough that they are not always readable as images. They appear, very matter-of-factly, as piles of cut paper and cardboard. Often they are suggestive of architecture but, for the most part, they look like little more than scattered parts, like someone sneezed on a jigsaw puzzle. Even the frantic use of typography is emptied of meaning, relegated to pattern and texture.

Even so, the works have a sense of depth that is impressive and fairly complex, mixing perspectival elements, such as vanishing points, and patterns that serve as backdrops, highlighting the figure-ground relationship. Formally, the work owes as much to abstract painting as it does to other collage. Letscher prefers lines and shapes of solid color to pictures, patching together his own forms that veer and wobble like an old barn.

In one image is a scrap from an old instruction manual for Tinker Toys. This is fitting, as it nicely sums up Letscher’s process; his use of simple parts and imaginative play are childishly brilliant.