A TASTE OF LIFE IN NEW MEXICO

WINE & CHILE

Story by Daniel Gibson

Photos courtesy of Ramona Sakiestewa

Original article published September 2019

The word creativity defines artist

During a recent interview in her airy, contemporary studio in Santa Fe, Sakiestewa seems surprised at the suggestion that she is perhaps the most versatile of all Native American artists working in the United States.

Decisive, willing to take huge chances, yet also very deliberate, methodical and modest, she responds, “I used to worry about ‘staying in my lane’ because most artists work in a single discipline, but I like trying everything.”

Indeed, the creative fires burn deeply in Sakiestewa. Though born in 1948, she is still embarking on new creative journeys after a career that has landed her work in major museums and collections worldwide, led to collaborations on massive architectural design projects, placed her side by side with the likes of Kenneth Noland and Frank Lloyd Wright, and filled countless homes with her beautiful works in textiles-from art tapestries to custom rugs-as well as her latest ventures in prints and other works on paper.

In September, the Santa Fe Wine & Chile Fiesta honors her, for the second time in two decades, as its featured artist. But that’s just the tip of her current distinctions and artistic output.

Two of Sakiestewa’s tapestries , “Nebula 22” and “Nebula 23,” the last weaving works she created before switching her focus to works on paper, are included in the traveling exhibition (with accompanying large-print publication) titled Hearts of Our People: Native Women Artists. The exhibit premiered at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, and will move on to other prestigious venues nationwide, including the Renwick Gallery in the Smithsonian Institution.

THE EARLY YEARS

The only daughter of a Hopi father and an immigrant German/English/ Irish mother, Sakiestewa was born in Albuquerque. “I always knew I would be an artist since I was seven, though I did not know exactly what that trajectory would be,” she says. “I got a little industrial Singer sewing machine when I was four and began making doll clothing, and by the second grade, I was making my own clothes for school. I was always good at making things.”

When she was 14 years old, Sakiestewa got a job working at an Indian “trading post” in Albuquerque on Central Avenue near 14th Street, where she oversaw employees significantly older than she when the owner, Tobe Turpin, Sr., left town on one of his frequent trips. “I learned a lot in that job,” she says. “It was a good job with so many different facets.”

From 1966-1968, she was enrolled at the School of Visual Arts in New York City, while working fulltime at Columbia University in the engineering department. “It was tough, but I was young and could do everything,” Sakiestewa says. “I was so excited to be there! It was all so new and fresh, and I made many friends, enjoying the contemporary art movement and new music underway in New York.”

Next came a period of travel, including stints in Mexico City; Palo Alto, Calif.; and Santa Fe. “Mexico City was actually the place where I found the best contemporary art scene in my life,” she says. Sakiestewa spent most weekends seeking out the rich architectural gems of Mexico City, as well as the wall murals often associated with these buildings, by artists like Diego Rivera, Jose Clemente Orozco and David Siqueiros. Her wide exposure to the buildings and their arts infused her unconsciously, and would go on to play major roles in her creative life moving forward.

A CALLING TO ART

Back in New Mexico, Sakiestewa spent several years as the minority arts coordinator for the state. Working with the Espanola Weavers Guild, she helped secure a major grant for the group and provided ideas on how and where they could host exhibitions. She realized that if she could help others launch an arts career, she could do so herself. “I could see the roadmap,” she says. “My arts administrative work was not personally fulfilling. I wasn’t making anything, or creating. So, I quit my job, borrowed money from my father-in-law to launch my weaving business and dove in. I managed to pay him back in three years.”

Sakiestewa began with functional work like placemats, table runners and custom rugs, decorated with abstract, flowing, ethereal designs based on patterns in nature and her Native heritage. She also taught herself how to master dying raw yarn with vegetal and mineral dyes, but realized working with commercially dyed fibers was far more practical in terms of time involved and what she needed to charge for work. She used vertical looms, the traditional form of Pueblo and Navajo weavers, but again found that modern, horizontal looms allowed for faster and more complicated work.

Her tapestry career thrived and led, eventually, to collaborative projects with artistic icon Kenneth Nolan and with the estate of Frank Lloyd Wright. To raise funds for the latter’s foundation, she executed 14 or so tapestries based on Wright’s original drawings, though he had already passed on. “It was very exciting,” Sakiestewa says. “I had to channel his spirit to get it right!”

In 1994, she was asked by the team designing the National Museum of the American Indian on The Mall in Washington D.C. if she would develop three “design vocabularies” for the interior and exterior of the building. The project consumed the artist for almost 11 years as she worked off and on, and she considers it one of the highlights of her life. When you enter this impressive, lovely, powerful building in native sandstone, you are passing through the doors Sakiestewa designed. When you sit down to a theatrical performance, you are looking at her curtain. When you enter the main rotunda, you are surrounded by her striking copper wall treatment. Everywhere you go, there she is. “It was so gratifying, because I got to work on a scale I could never afford,” she says. “But more importantly, it has been so satisfying to see that Native people from all over feel they own it, that it is their place and a sacred space.”

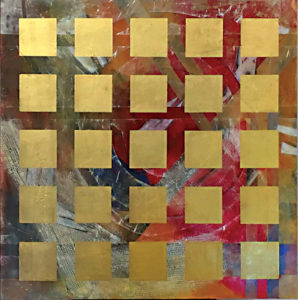

Nebula 19

Many other architectural projects followed, from designing floor carpets to core master planning, including a project in Kurdistan, for Marriott Residence Inns in California, the Tempe Center for the Performing Arts, and the Chickasaw Cultural Center in Oklahoma to name a few.

Yet despite her success first in textiles, then architectural design, today, Sakiestewa is busy producing beautiful works on paper, paintings, watercolors and prints. Printing based on her original works is largely done by professionals like Ron Pokrasso, Michael McCabe and the Tamarind Institute in Albuquerque. She is also cutting up prints, then hand-stitching elements back together, literally tying together her past media and present, and producing household goods embellished with her distinctive nature and Native-themed designs.

Way before this point, most artists would have said, Tm there.’ But as, a life-long learner with a home jammed with books, Sakiestewa notes, “People tell me I’ve ‘made it’ and ask why I keep on. But you never ‘make it’ nor do it alone. I had long wanted to pursue other media and felt I had done my very best work I could ever do with my last tapestries. So, I turned to works on paper, and now product development. You have to keep working at it. You age out, even as an artist. There’s no stopping, not for me.”