Elyssa Goodman

Feb 8, 2019

Original article at Artsy.net

“I’m not magical realism, Surrealism, nothing like that. I’m Graciela Iturbide,” the photographer stated in a 2017 video. Considered one of the greatest contemporary photographers of Mexico, her home country, and of all of Latin America, Iturbide rejects the label of magical realism for her work. “No, magical realism you invented for García Márquez, Vargas Llosa, for the ‘boom’ of literature, and to be able to better sell books,” she continued. As an artist, she hopes to be defined simply as herself.

In a career spanning over 50 years, and with photographs from her beloved Mexico, as well as India, Argentina, Cuba, and the United States, Iturbide became known for black-and-white images that raise documentary photography to a poetic plane. Her images are only magical realism in that they capture the magic of what exists in front of us, or in places we have not yet seen. A new exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, entitled “Graciela Iturbide’s Mexico,” features 125 of Iturbide’s images from her five decades in photography.

Graciela Iturbide, Lagarto (Alligator), Juchitan, Oaxaca, 1986. Etherton Gallery

Graciela Iturbide, El Gallo (The Rooster), Juchitán, Oaxaca, 1986. Etherton Gallery

Iturbide grew up as the oldest of 13 children in a Roman Catholic family, and she was first exposed to photography by her father, who photographed her and her siblings. Iturbide had hoped to be a writer, but due to her family’s conservatism, she wasn’t allowed. That desire for lyricism appears in her pictures instead. “What I essentially look for everywhere is poetry,” she once said.

Iturbide married at 19, and in three years, she had three children; her second child, Claudia, passed away at just six years old. Shortly after, she and her husband divorced, and a distraught Iturbide returned to school at Mexico’s Centro Universitario de Estudios Cinematográficos. She studied cinematography, hoping to become a film director, but her family did not approve. “They are bishops and archbishops and you can imagine what I am to them: the crazy one who studies film and gets divorced,” she told the Los Angeles Times in 2017. But soon, Iturbide met professor Manuel Álvarez Bravo, one of the defining photographers of both modernism and 20th-century Latin America. “He was not just a photography teacher. He was a teacher of life,” she said in a video for MFA Boston. “Above all, he taught me that I had to have time.” From 1970 to ’71, Iturbide was his achichincle, his work assistant, and with him, she began to explore more parts of Mexico.

Graciela Iturbide, Mujer Ángel, Desierto de Sonora (Angel of the Desert), Mexico, 1979. Etherton Gallery

Towards the end of the decade, Iturbide began photographing the indigenous communities of Mexico, commissioned by the Ethnographic Archive of the National Indigenous Institute of Mexico in 1978. She met the Seri people of the Sonoran desert, forming a rapport with their community. It was there that she made one of her most famous images, Mujer Ángel (1979), or “Angel Woman.” In the photograph, a Seri woman walks near the area’s caves, long dark hair at her back and a boombox at her side, her skirts frozen in motion. “For me, this photograph represents the transition between their traditional way of life, and the way capitalism has changed it,” Iturbide told The Guardian in 2012. “I liked the fact that they were autonomous and hadn’t lost their traditions, but had taken what they needed from American culture.” Iturbide has acknowledged the image as one of her best photographs. It also later became the cover of rock band Rage Against the Machine’s single “Vietnow” in 1996.

Graciela Iturbide, Nuestra Señora de las Iguanas. Juchitán, México, 1979. Rafael Ortiz

Perhaps Iturbide’s most famous image, Nuestra Señora de las Iguanas (1979), or “Our Lady of the Iguanas,” is a portrait of a Juchitán woman wearing a crown of iguanas on her head. The image became one of the town’s most famous identifiers, inspired a statue there, and eventually became one of the country’s most iconic images. The photograph is also placed on road signs in the city, as well as on bottles of Mezcal (without Iturbide’s permission), and has been the subject of murals in Los Angeles.

During this time, Iturbide established a style for herself: Her signature high-contrast, black-and-white images brought a sense of the extraordinary to the mundane. She gave a voice to communities that were often ignored, but moved beyond reportage, sharing the richness of their cultures. This led to more commissioned work around the world. “As an artist you need to move on, you need to try new things,” she once said. “I can’t take pictures of Juchitán and Juchitán over and over again. And in the end, photography for me is just an excuse to get to know the world.” Iturbide had her first international solo exhibition at Centre Pompidou in Paris in 1982; since then, her work has been exhibited in solo shows at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and the J. Paul Getty Museum, among others.

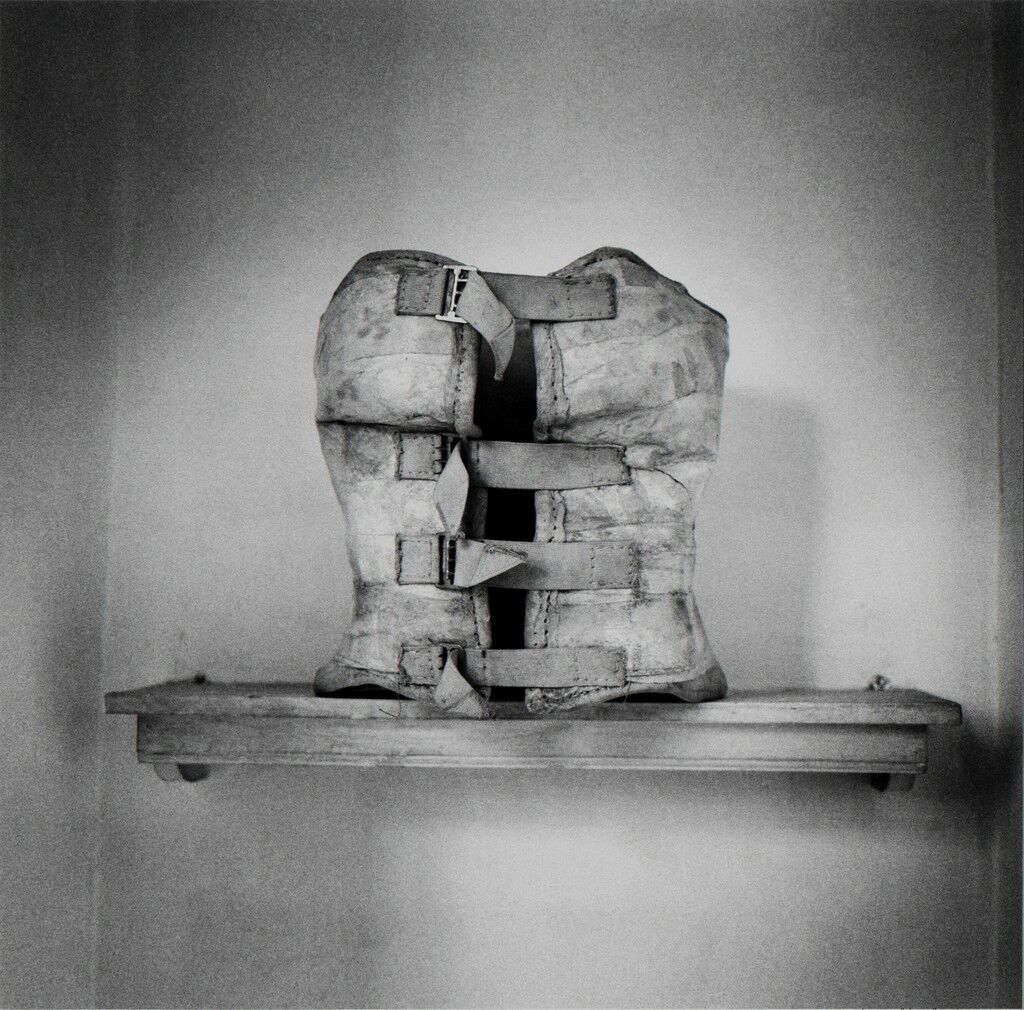

Graciela Iturbide, El baño de Frida (corset en el estante), Coyoacán, México, 2006. Ruiz-Healy Art