There happens to be a Wassily Kandinsky exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum in New York, and it is to Kandinsky I would compare Linda Whitaker’s freewheeling sense of color. In many of her oil-pastel-on-paper drawings—her works can’t really be called paintings although they are indeed painterly—there is also a similar ability to abstract essential forms from nature and re-present them as examples of “shoot-the-works modernity,” a phrase I’ve borrowed from Peter Schjedahl’s recent New Yorker review of the Kandinsky show.

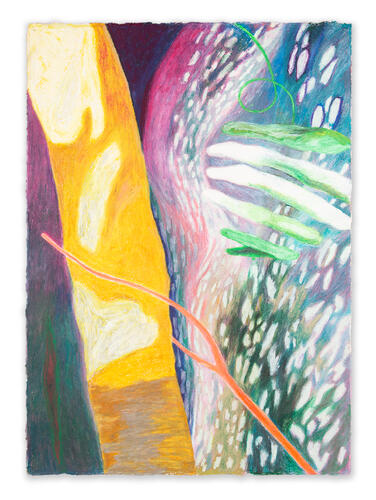

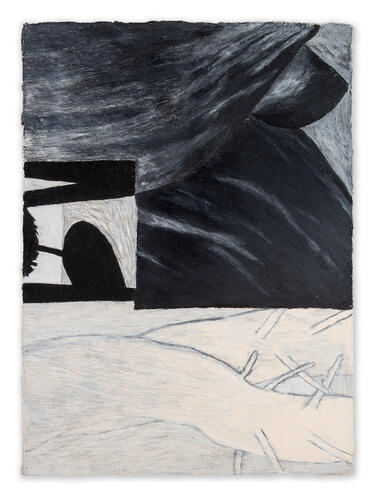

Seeing yet another exhibit of landscape images from New Mexico might be a tad off-putting if Whitaker hadn’t managed to convey her own unique vision of Taos Gorge, a valley in Mora, stacked hills, a winding river, or a hallucinatory sunset that is mostly yellow, green, and chartreuse. But perhaps the sunset is something else—simply clouds of acid colors at play in the fields of someone’s vivid imagination. And, in the work “Visalia,” just what is that strange pink and white finger-like extension pointing away from a teal blue and black horizon line?

To say that Whitaker’s palette freely tweaks the landscape genre is only part of the story, however. These relatively small images—no bigger than eleven by twelve or thirteen inches—are dense with an intriguing vocabulary of shapes depicting landmass, shadow, bolts of lightning, atmospheric conditions of various sorts, cloud cover, and whatever other forms Whitaker sees and then reinvents for pictorial purposes. Whitaker has a succinct ability to push her landscape material into the realm of abstraction without sacrificing her original en plein air matrix.

Another interesting facet of this work is that these drawings are over twenty years old. That said, the images are vibrant and they reveal an up-to-date spontaneity that is altogether refreshing and not a little irreverent in Whitaker’s refusal to go the way of the sublime. In “Okolana,” for instance, the artist’s rose-colored sky is less about the radiant pink and fuchsia sunsets we often witness in the Southwest than an example of the artist’s dashing color sense and her talent for creating startling contrasts. Whitaker doesn’t try to blend colors—she lets them sit next to each other so that foreground and background, sky and land, trade places in the push and pull of her surfaces. The artist’s freedom from anyone’s expectations leads to the viewer’s delight in work that is both accessible and sophisticated.

It’s a shame that Whitaker’s art is a thing of the past. As I understand it, she no longer is a practicing artist. But these quirky, snazzy drawings are a welcome addition to the long history of aesthetics grappling with the geography of New Mexico and attempting to do it justice. Whitaker’s vision has its own spicy immediacy and originality; she demystifies the landscape genre and gives us some highly charged, personal impressions of the land and the sky come hell or high water.