Elephant and Artsy have come together to present This Artwork Changed My Life, a creative collaboration that shares the stories of life-changing encounters with art. A new piece will be published every two weeks on both Elephant and Artsy. Together, our publications want to celebrate the personal and transformative power of art.

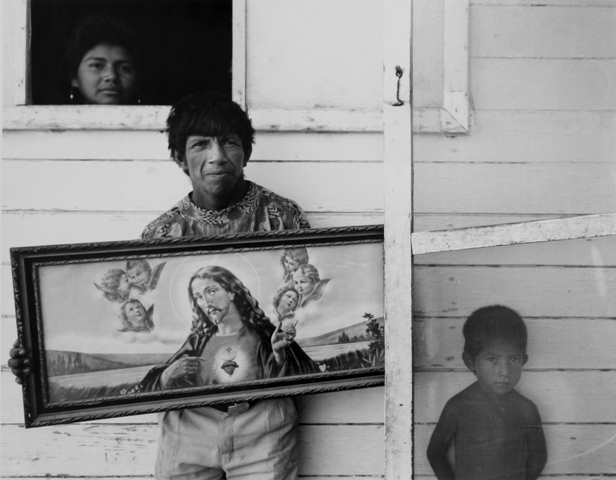

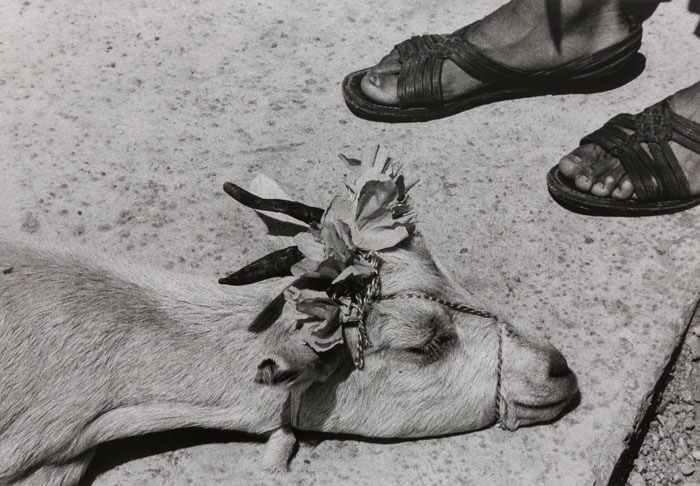

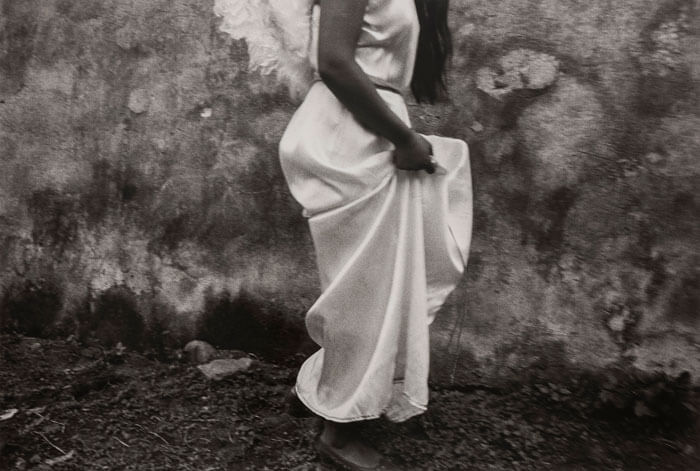

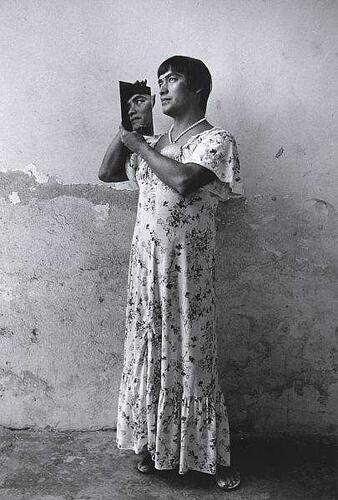

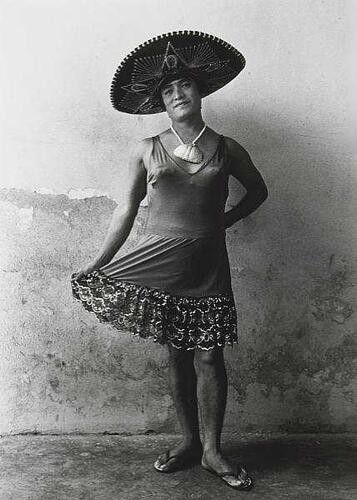

Graciela Iturbide spent around 10 years photographing Juchitán de Zaragoza, a small town in Oaxaca. Juchitán is often referred to as a matriarchy—primarily because women control its economy—and Iturbide’s friend, the artist Francisco Toledo, had asked her to capture it. She did, and so was born one of her most iconic images: Nuestra Señora de Las Iguanas (Our Lady of the Iguanas), Juchitán, Oaxaca (1979).

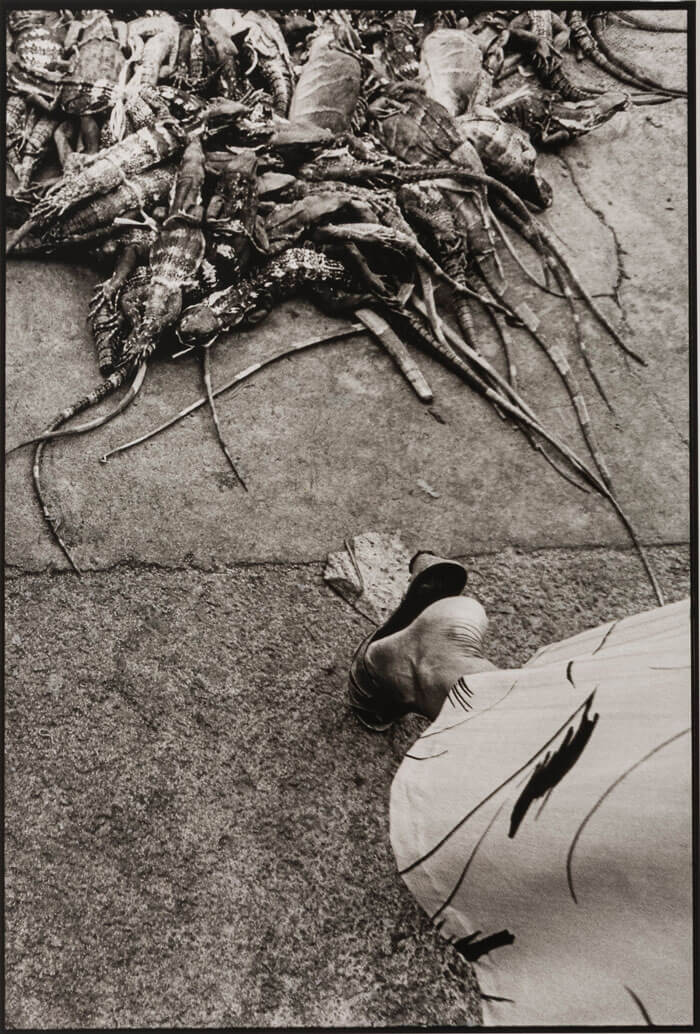

In the gelatin silver photograph, Iturbide captures Zobeida, a woman with a crown of iguanas perched on her head. The woman looks past the camera in a self-assured, almost defiant way. The background is slightly out of focus to keep the attention on this woman, caught somewhere between the everyday and the mythical.

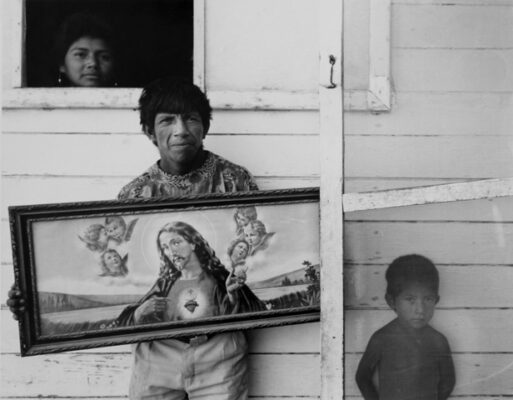

I first encountered this piece—and Iturbide’s work—by accident, at a Santa Monica gallery while I was in the area for another writing assignment. As an art history student in college and grad school, I’d grown comfortable with wandering into white gallery spaces and high-ceilinged museums. I’d also accepted that the artworks on the wall would rarely feature certain people—people from my own Latinx heritage (I am a first generation Guatemalan American), but also other communities of color, indigenous communities, and Black communities.

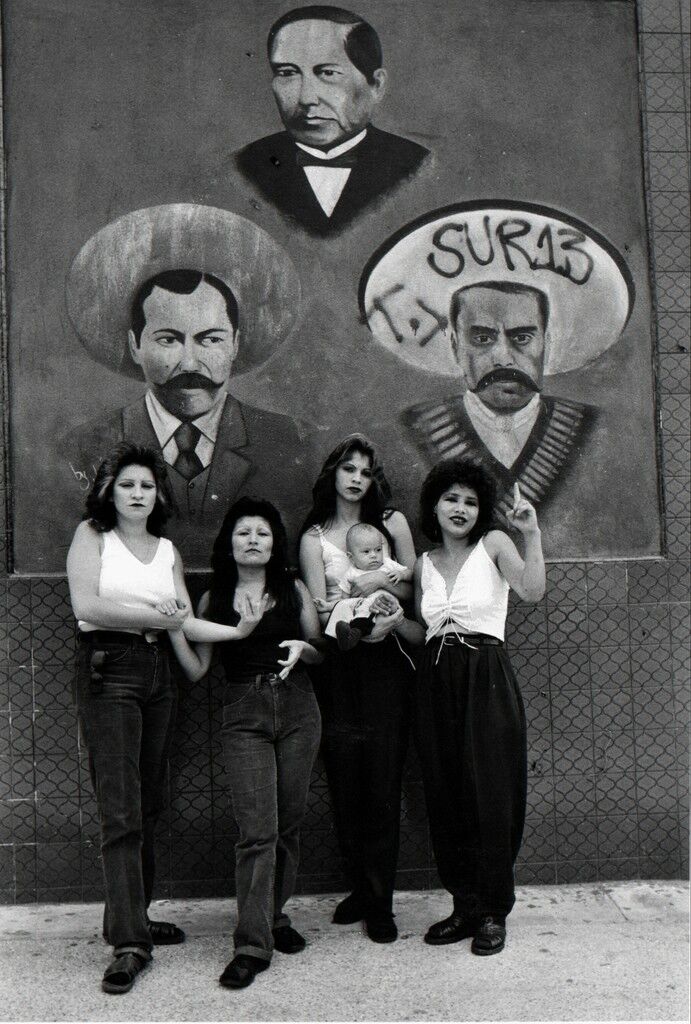

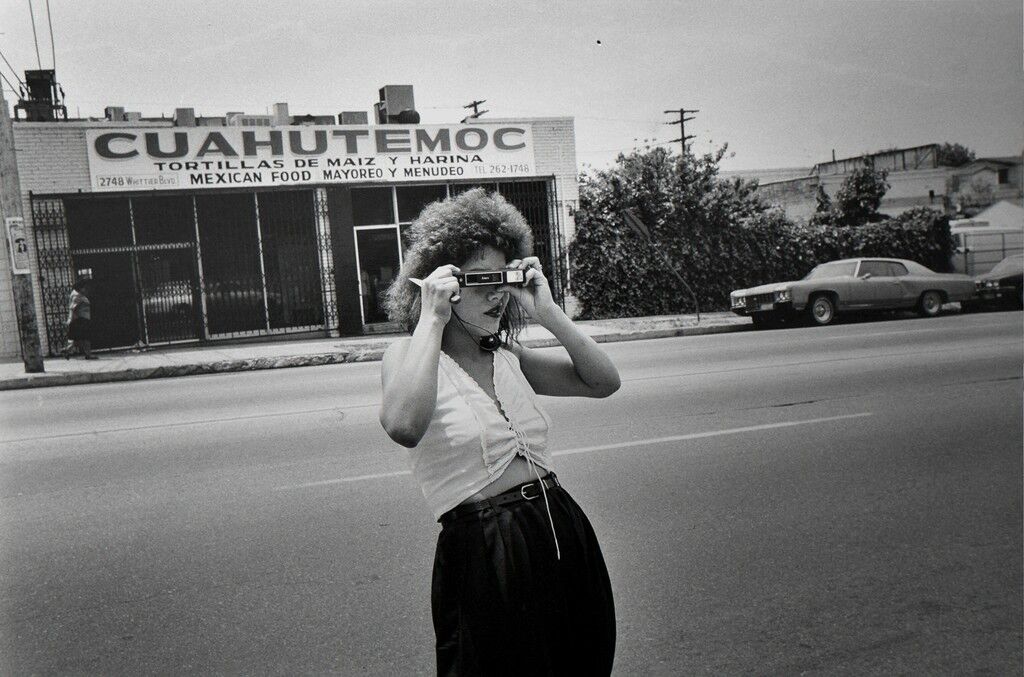

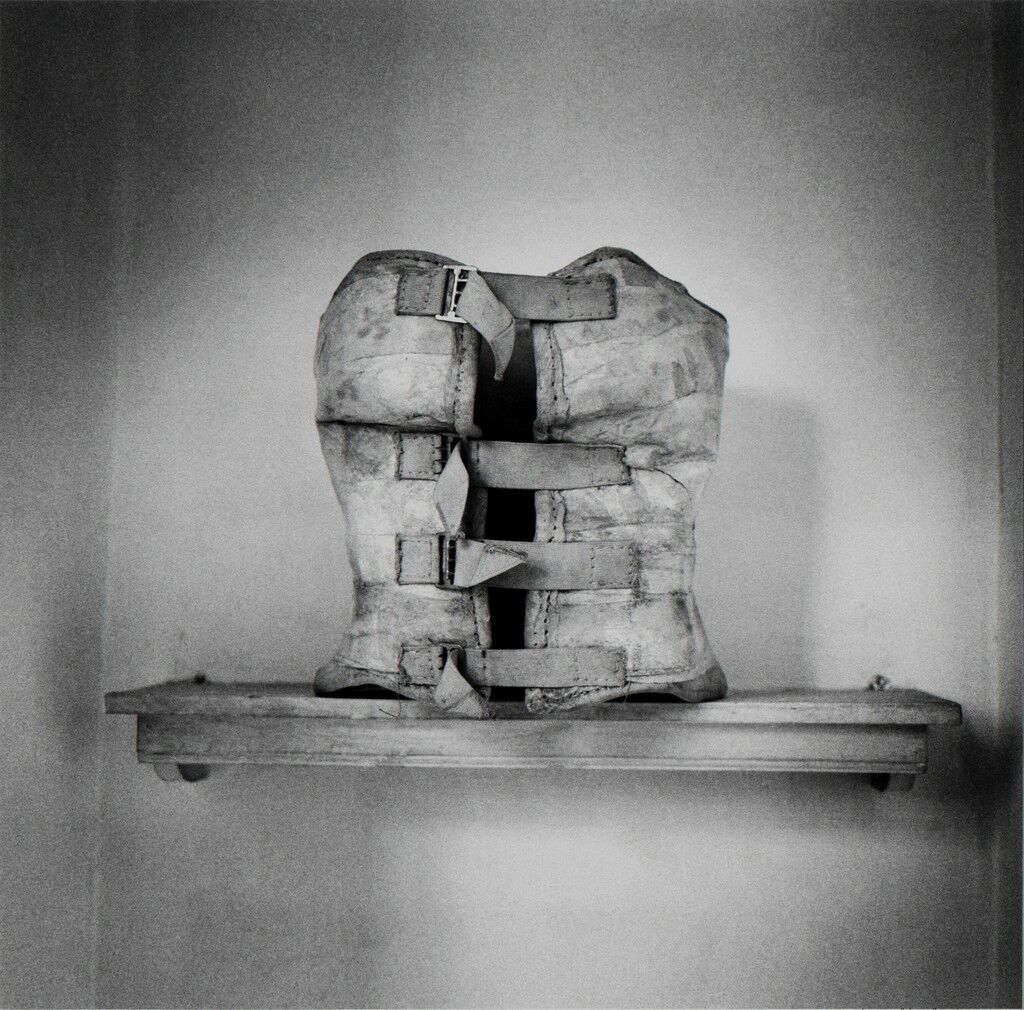

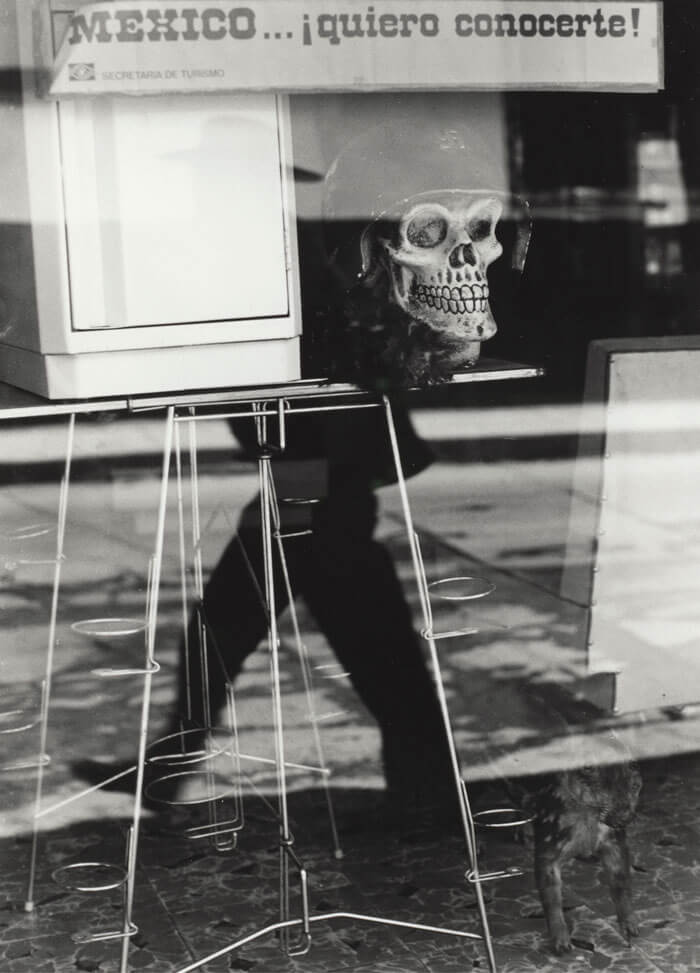

After finishing my master’s, I found myself reflecting on the place of Latina photographers within the art world. The work of artists like Laura Aguilar and Christina Fernandez were a revelation to me, and now, Iturbide’s photography hit me with full force. In her pieces, I saw death captured matter-of-factly; nature transformed into metaphor; people in East Los Angeles juxtaposed against the backdrop of a fraught America.

I was ashamed I didn’t know more about Iturbide’s work. So much of my art-historical education—the images in textbooks, the works I kept seeing over and over in permanent collections—embedded other photographers into my memory. Those artists reflected realities in a way that pulled me in, but still left me with the feeling that I was right outside of the frame.

Here was a woman of color capturing her subject in a sensitive manner, tracing her own roots. Iturbide was working in the mercado on the day that she saw Zobeida, the vendor with a halo of iguanas. In the image, Zobeida isn’t exoticized or examined. Iturbide managed to delicately craft a balance in which her subject appears timeless, yet humanized. She carries the iguanas out of practicality, their beady eyes and drooping jowls soon to be made into stews and tamales.

The Juchitán community dubbed the photo of Zobeida “The Juchitán Medusa.” It becomes, in a way, a total departure from many art-historical and mythological depictions of the snake-headed woman. Here, Zobeida holds onto her power, plucking and adding iguanas to her crown at her whim. No Greek “hero” in sight.

In the biography Photographic: The Life of Graciela Iturbide, author Isabel Quintero writes: “Remember, everything for Graciela is complicit. She doesn’t work alone.”

In the photograph, we look up at Zobeida, her chin creating a shadow over her neck. We see the iguanas from all angles; just a hint of her hair peeks out from beneath their bodies. Iturbide constructs this image for us, but she allows for Zobeida’s own interiority to come through.

As a Latina, Iturbide’s artistic practice has encouraged me to pursue my own creative passions and search for answers about my own cultural history. Studying the image again at home, I remembered the women I saw in Antigua, Guatemala, who braided colorful thread through tourists’ hair in exchange for a few quetzales. As a teenager, I sat for one of the women and took photos of the town as someone passing through, not someone familiar with the area.

I remembered, also, the moment when a man brought his pet iguana onto the bus in South Los Angeles, my hometown. He had a leash on it and the reptile kept eerily still on the floor, unfazed. A thread connects me to California and Guatemala, but one end is pulled more taut than the other. I haven’t been to Guatemala in more than a decade.

Nuestra Señora de Las Iguanas became a motivation for me—to keep mining my own personal history; to see the validity in my narratives, as both a writer and an art lover. Zobeida’s humanity extends beyond the frame of the photograph, asking that we look a little closer.