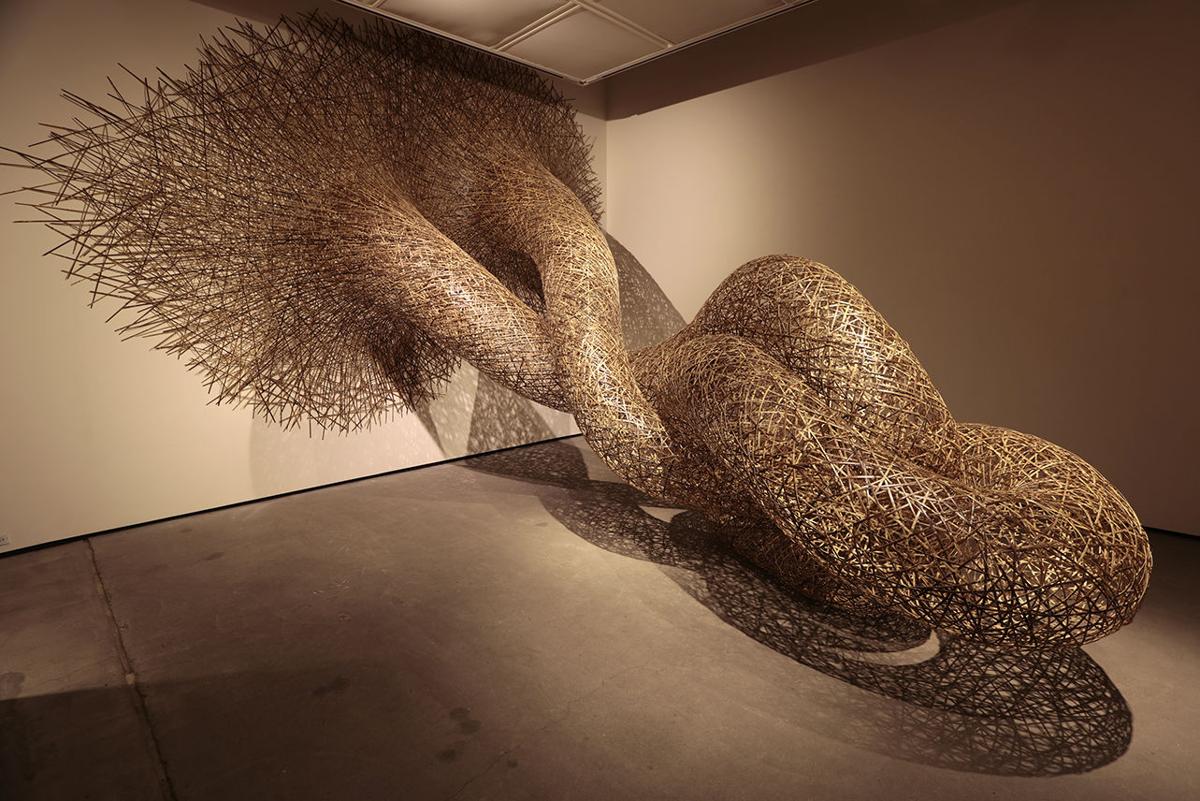

Tanabe Chikuunsai IV, site-specific installation at Tai Modern, photo Gary Mankus

Tanabe Chikuunsai IV, site-specific installation at Tai Modern, photo Gary Mankus

The snaking, tubular form, made entirely of bamboo, extends from a point on the wall and curves downward to the floor. Wrapped around itself, the form rises again from the floor to a termination point on the same wall. There, thin strips of the bamboo splay out against it like a flattened basket, as though it were merging with the wall itself.

On this day in late July, bamboo artist Tanabe Chikuunsai IV is more than halfway through construction of this site-specific installation. The basic form is there. Now it’s just a matter of adding and subtracting to fill out the structure — which measures 17 feet wide, 16 feet deep, and 13 feet high — and give it a less skeletal, more uniform appearance.

Tanabe Chikuunsai IV is currently on display at Tai Modern.

Born Tanabe Shˉochiku in 1973, the artist earned the name Chikuunsai, which means “master of the bamboo clouds,” in 2017. The gallery, where the installation is on view through Aug. 24, has shown work by all four family members to bear the name Tanabe Chikuunsai over the course of the gallery’s 20-year history. The artist created the sinuous piece to honor that legacy, as well as its commitment to bringing the art of bamboo to American audiences.

With Tai director of Japanese art Koichi Okada translating, Chikuunsai gestured to the writhing form and said: “Here’s the origin of bamboo art in the West, which will continue to move toward the future.”

For this installation, the artist is using something called tiger bamboo because of its distinctive patterns: straw-colored stalks flecked with brown. Approximately 8,000 of the bamboo strips were shipped by crate to the gallery from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

“It’s a very rare material,” he said of the bamboo, which is only found on one mountain in a remote region of Japan’s Kochi Prefecture. “Even on the specific mountain where this type of bamboo grows, only one out of 20 have this pattern. This particular bamboo is very pliable. That’s the reason I like to use this material for my installation work.”

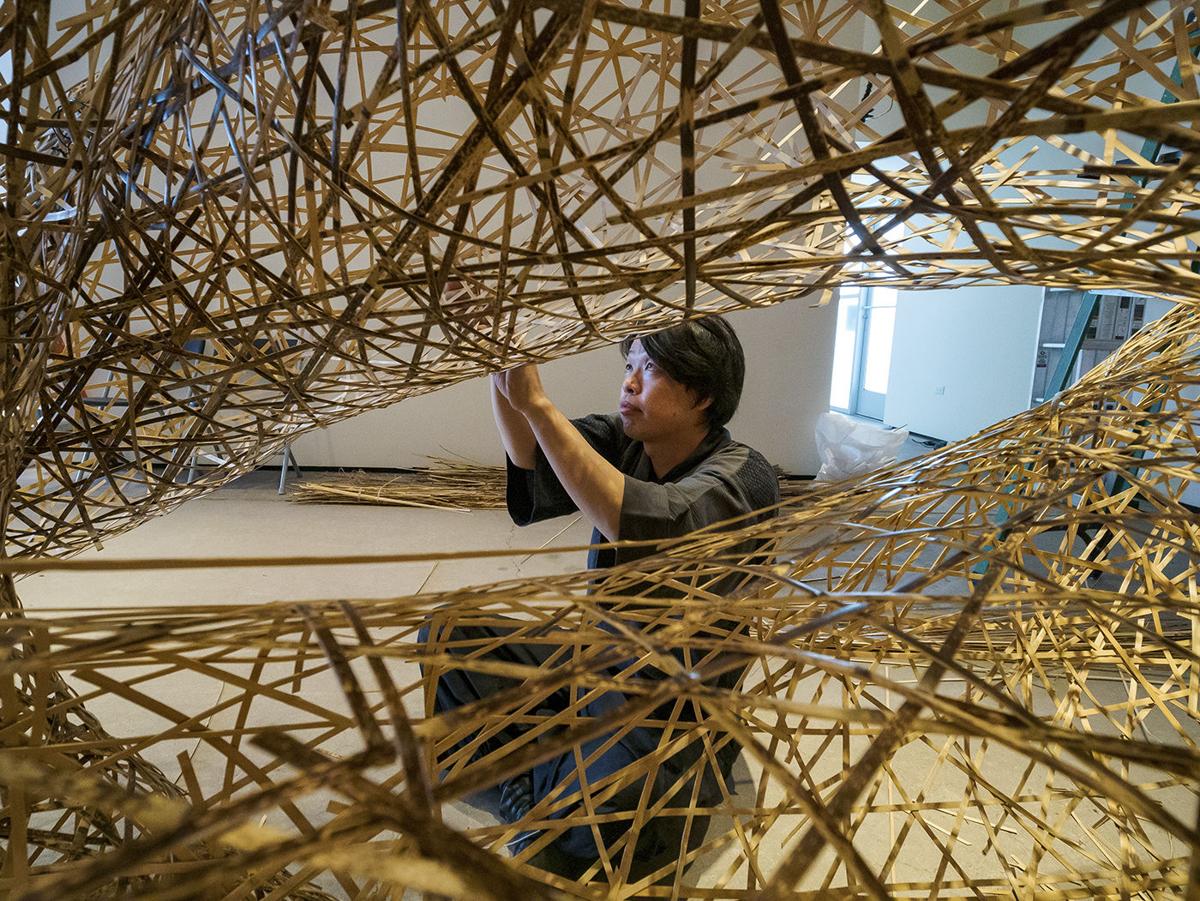

Chikuunsai arrived at the gallery on July 18 to take measurements and assess the space where the piece would be constructed. The work began on the installation the next day. Through the weekend, Chikuunsai and two apprentices, Kayoko Sano and Tomo Uesugi, worked quickly but steadily from 9 a.m. to 7 p.m., giving shape to the organic structure by braiding the strips, which are about a half-inch wide but vary in length from 4 to 10 feet. Other than hooks set into the walls, which give Chikuunsai an initial anchor for the work, the tiger bamboo is the only material used.

All of Chikuunsai’s installations are similar in appearance and look like bulbous, twisted tree limbs or roots. The major difference is the scale, which is determined by the dimensions of the spaces where they’re installed. At Tai Modern, he starts by taking the flat pieces of bamboo and bends them outward from the wall to form the beginnings of a funnel shape, about three feet in diameter. It will eventually grow into the latticework creation that winds through the space, held together only by an inherent tension.

“I don’t use adhesive or glue or anything,” he said. “The basic structure is hexagonal plaiting.”

When he’s filling in the gaps with strips of the bamboo to flesh it out, he uses another technique known as arami, which he calls a kind of random, open form of plaiting. “It’s one of the traditional techniques passed down from generation to generation in my family,” he said. “I’m using my family’s traditional techniques to create something entirely new.”

The gallery plays a prominent role in promoting contemporary Japanese bamboo artists in the United States who, like Chikuunsai, use the medium for sculptures that range from simple and rustic in appearance to stately and intricate. But the art of bamboo is not widely practiced in Japan.

“I think he sees part of his responsibility as a Chikuunsai to keep alive the styles, techniques, and artistic voice of previous generations,” said gallery director Margo Thoma. “Historically, there might have been a greater awareness of bamboo artists in Japan, but today, not a lot of people there are aware of the art form. In terms of international exposure, he’s taken it to a new level.”

If Chikuunsai’s work seems innovative, it lies less in the techniques used than in how he uses them. His smaller bamboo works, several of which are on exhibit in another room, range from sculptural but potentially functional (flower baskets, for example) to purely abstract sculpture. In both cases, they’re made using tried-and-true methods, such as mat plaiting, which creates a dense interwoven structure. He also creates smaller works using other materials like black, arrow, or madake bamboo. “Currently, I use about 10 different types of bamboo, depending on what I want to achieve,” he said. “Tiger is suitable for larger work, but it’s not good material for smaller work.”

Chikuunsai is most radical when it comes to the colossal scale of his installations, such as his recent project The Gate, a cyclonic floor-to-ceiling installation at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, created in 2017.

“The material you see here today is the same material I’ve been using for seven years,” he said. “The bamboo has traveled to so many different parts of the world.”

The exhibition is also showcasing sculptures from Chikuunsai’s Disappear series. Each one was made in collaboration with Kaijima Sawako, an assistant professor of architecture at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design. Using computer software, Sawako created intricate designs based on mathematical algorithms that were then 3D-printed. Chikuunsai recreated the models in bamboo, matching the delicate and precise forms of the printed models. “The aim of this collaboration was using cutting-edge modern technology and the tradition of craft art,” he said. “The actual process of making this with bamboo is really low-tech in some ways.”

Chikuunsai’s mastery of bamboo is evident in the myriad forms and styles of his work. It’s hard to believe that it was all made by the same artist. Even if he didn’t create large-scale installations, he might still be considered a pioneer for bringing bamboo artwork out of the realm of craft and into the arena of fine art. But he insists he’s not the first one in his family to challenge convention. “Even the work of the second generation, if we reflect upon it with today’s ideas about contemporary art, may look traditional. However, the second Chikuunsai moved toward a more open style of work, which was extremely radical and contemporary during that time period. My family carries some of the traditions and skills. At the same time, finding new challenges has been our family philosophy.”

details

▼ Tanabe Chikuunsai IV

▼ Tai Modern, 1601 Paseo de Peralta, 505-984-1387, taimodern.com

▼ Through Aug. 24

▼ To see a time-lapse video of the installation’s creation, go to YouTube

Tanabe Chikuunsai IV at work, photo Incredible Films

Tanabe Chikuunsai IV at work, photo Incredible Films