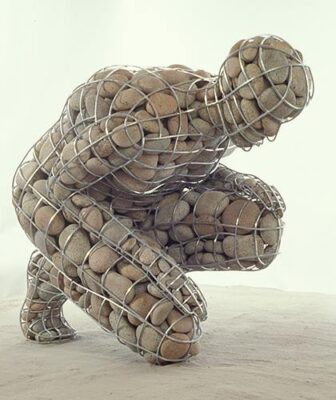

Anodized steel, hand-selected river rock from the Truckee River

Dimensions: 54” x 58” x 40”

Location: Front Entrance to the NMA

Acquisition: Courtesy of the Artist and Funded by the City of Reno and the Nevada Museum of Art Volunteers In Art

Cairn, the most enduring of all the NMA sculptures, is popular with all age groups. It has greeted visitors to both the old and the new museum for many years. It is unique in that it is a “site specific” sculpture, created just for the NMA in 1998 by artist Celeste Roberge. The word cairn means “mound of stones erected to mark a site.” Roberge creates welded steel figures and fills them with various geologic materials gathered from the site local to where the sculpture is installed. Cairn represents a continuation of a series of rock figures that Roberge has been creating since the 1980s. Some are standing, some rising, and some walking. Her other cairns are rock-filled steel frameworks in the shape of globes and columns, and quarried rocks arranged as benches and outdoor “living room furniture.”

In 1999, the NMA presented an exhibit titled “From Exploration to Conservation: Picturing the Sierra Nevada” in which Roberge created a video installation commissioned by the museum that featured a tent and rocks in a stream of endlessly flowing water. Titled “Mountains and Rivers Without End,” it was a rocky streambed with a simulated “flow” of gurgling water.

Celeste Roberge (b. 1951) is an Associate Professor of Art and Sculpture Area Coordinator at the University of Florida in Gainesville. Her works are in numerous public and private collections across the U. S., mostly on the East coast. She lives and works in Gainesville, Florida, and South Portland, Maine.

At Runnymede Sculpture Farm in Woodside, CA, there are two Roberge Cairns: “Rising Cairn” and “Walking Cairn.” The following is a statement from the curator there: “These are our two most commented-upon pieces. People respond to these works viscerally and immediately. There is a dignity to these two pieces which draws the viewer into a contemplative space. Both pieces are female forms and modeled after Roberge herself. They are filled with river rocks and play upon the idea of ‘”figurative.’” We usually think of figurative sculpture as being carved out of rock: these are composed of rock. It’s as if you’re looking inside the people themselves; you see their viscera, their muscles. And the sculptures draw attention to the paradox of living: we live both inside ourselves, with emotions and thoughts, and we live outside in the world through actions and communication.”

About Cairns:

A basic cairn is a single stack of rocks essentially made to mark a path, territory, or site, or meant to be a tomb marker. The intent is utility and meaning rather than art. Those who place them are thinking of those who will come after. Those who find and follow them are trusting the travelers who went before.

Cairns of various types are found throughout the Neolithic world and recall early representations of women. Stacked or balanced, these offer places and moments for reflection, or meditation. Balanced stones are designed to stand for a long time without falling. Modern day hikers often refer to them as “trail ducks” when the top rock is larger and points the way at a turn. Some National Parks have rules of “rock etiquette” about cairns and the making of rock sculptures or the disruption of rock formations. Death Valley National Monument in California is one such place. Acadia National Park in Bar Harbor, Maine, also has an extensive system of cairns and rules about their construction. However, at Peace Cairn in Ireland (established in 1993) people are encouraged to bring a small rock or stone to add as a personal statement to symbolize the laying down of primitive weapons—turning them into building blocks of a better future.