Fairy tales are always being co-opted. The famous brothers Wilhelm and Jacob Grimm who, in my day, were often mistaken to the originators of all fairy tales (whereas now Nickelodeon is more likely to be the mistaken originator), simply collected and interpreted stories they gathered in Germany for Kinder- und Hausmärchen (Children’s and Household Tales). The collection was seminal only in its scholarly application. The Brothers Grimm, linguists and philosophers—and only accidentally folklorists—were subject to plenty of criticism during their time and were frequently accused of misrepresenting or altering tales that had been handed down through oral tradition within the loose conglomeration of villages and tribal alliances that eventually became Germany.

A quick glance at the Grimms’ versions of “Cinderella” (“Aschenputtel”) or “Little Red Riding Hood” (“Rotkäppchen”) reveal much darker and more morally ambiguous tales than those eventually popularized in American culture. Even as Disney has continued to push sanitized polarities of right and wrong onto generations of mesmerized youth—who, at this point, are practically connected to their DVD players by an IV drip—writers, librettists, filmmakers and artists have been reinterpreting, co-opting and dissecting fairy tales with regularity. At times, it almost feels like a standard trick for confronting the blank page: When lacking an idea of one’s own, there’s always popular folk fodder to rehash. But just because the fairy tale is an easy target, doesn’t mean an exhibition such as the current Once There Was, Once There Wasn’t: Fairy Tales Retold can’t be intelligent and capable of inducing, in the jaded adult mind, the familiar glee of encountering the same icons in childhood.

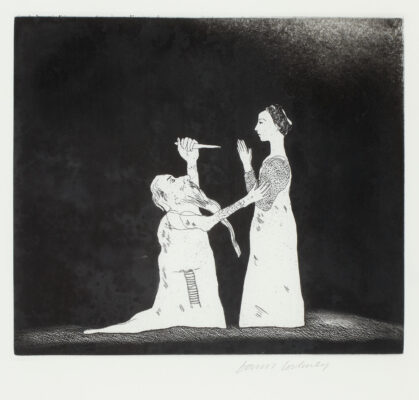

On view at Eight Modern, the exhibition sucks several artists into its orbit (perhaps a few more than a focused display demands), and indulges the practice over a span of decades. One wall is dedicated to David Hockney’s “Six Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm,” a suite of aquatint etchings from 1969 that remains fresh, elegant and kinkily alluring. His flat, graphic approach, dry humor and dark sensibilities do well at plumbing the original complexity of the tales recorded by the Grimms, as opposed to the more popular and dumbed-down versions.

Distributed around the gallery are various works by Kiki Smith that investigate folk archetypes, quaint legends and crone lore to mixed degrees of success. Works by Richard Tuttle and Jim Dine are elegant in and of themselves, but don’t push far enough into the territory to reveal any intriguing geography among such universal signifiers as such tales invoke. Pieces by Elizabeth Layton—a depiction of the elderly Cinderella whose fairy tale has turned to bitter reality—and Paula Rego—a haunting etching dubbed “Goosey Goosey Gander”—are successful and appropriate, but maddening for the lack of further work. Rego’s nursery rhyme print is worth a visit, but it’s a shame—given the theme—that one of her more broadly probing and more precisely implicating illustrations of Snow White, Peter Pan or Pinocchio couldn’t be located. Jessica Abel, creator of the ArtBabe comic, and a contemporary urban folk tale creator in her own right, is a welcome addition, although she could have been more celebrated in the presentation.

New York artist Adela Liebowitz puts a good foot forward, especially in, “The Awakening,” a large oil and linen work, in which three brutally creepy young girls conduct a mysterious congress in a sparse, blue-tinged woodland. The show’s real strength, however, is sourced from imminently capable photogravures of David Levinthal and the illustrative, fierce genius of Peregrine Honig and Fay Ku.

Levinthal’s images, which use kitschy pot-metal figurines to enact narrative moments, form Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, maraud the gristle of the spine with the nauseating tingle of genetic and cultural memory instilled by the oft-hidden violence and perversity of our country’s past. The series, from which only one piece is hanging—the remainder needs to be viewed with assistance from the gallery staff—is remarkably printed by Landfall Press.

Executed with similar skill by the Lawrence Lithography Workshop, is Honig’s series of prints, “Father Gander.” Honig, whose alarming illustrations vacillate from sly to violent, plundered early children’s book techniques, 1950s homemaker graphic sensibilities and Barbarella-style babedom to sexualize, dramatize and traumatize Snow White, Little Red Riding Hood and Hansel and Gretel. Each are put into positions of uncomfortable addiction, self-destructive flooziness, unflattering psychological reflection, etc., until their magic auras become as cheap and tainted as the darkest secrets and despairs that each viewer drags into the gallery of his/her own accord. Honig’s aesthetic is so keen, her hand so precise and her symbolic cuing so adept, that her unerring dismemberment of contemporary culture through fairy tales is a fire in the brain and a sucker punch in the gut all in one moment of pained bliss.

Using a similar rope-a-dope technique of finding pleasure in discomfort, Fay Ku (who has been offered a residency at the Santa Fe Art Institute in the upcoming cycle) employs a recurring cast of young girls, sexless but sexualized, who experience mythic and legendary circumstances in animated states of violence, vengeance, curiosity or hyper-ennui. Working in ink, watercolor and graphite, Ku leaves big sheets of paper mostly barren, thereby instilling sudden and ferocious energy into her combative and difficult scenes. In “Furies,” the young denizens of her world, in playhouse-appropriate martial garb, attack and dismember a scatter of harpies. In “Top Girl,” they turn upon each other in an acrobatic and archery-filled game of king of the hill.

Once There Was, as an exhibition, breaks apart the comforting epilogue of a happily ever after, not only on paper or in fable, not only in the modern world at large, but very likely right outside the window right now and within the core of our individual, meandering, complicated lives.